Metro Manila’s first few days under General Community Quarantine (GCQ) saw a deluge of commuters being stranded with no sufficient public transportation. But the urban commuter’s burden has long been an issue even before the pandemic.

Caryn, a resident of Tondo in Manila, recalls a particular incident that stood out in her more than twenty years of commuting. “Once, I was in Pasig when the MRT broke down and we were advised to take the bus across the street. I was so surprised to find out there wasn’t a bus stop. There were no lines—it was a free-for-all kind of thing. People grabbed the railing and pulled themselves up onto the bus, while the conductor kept yelling for people to hurry up because the traffic enforcers were coming.”

Aloy, who’s been commuting since she was twelve and is now a mom, has a collection of horror commuter’s stories. “Around 2003, I was sitting in a taxi in the middle of traffic, painfully aware that I was missing my friend’s wedding to which I was supposed to be the lector. In 2005, when MRT was getting more crowded, I remember being forced to press against a total stranger—male, as luck would have it. In 2016, I was stuck in one of those triple whammy carmageddon nights of floods, mall sale and payday. I was forced to stay over at a friend’s home until 11 p.m. before I could go home to my family, which included a breastfeeding baby. I think about all the time traffic has stolen from me and my family, and I find it unacceptable.”

Biker wears a face shield attached to his helmet (Photo by Jire Carreon)

Biker wears a face shield attached to his helmet (Photo by Jire Carreon)

Hitting the road

In 2010, the World Bank noted an increase in energy consumption from the Philippines’ transport division, making up about 37% of the country’s total energy consumption—most of it coming from road transportation.

But with the declaration of the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) two months ago, people were discouraged from leaving their homes and public transportation was banned, resulting in empty roads. With essential businesses such as hospitals, pharmacies and food markets continuing operations, employees and consumers who didn’t own cars rode bicycles or walked.

Danielle Guillen, an urban transport planner and professorial lecturer at the University of the Philippines Diliman’s School of Urban and Regional Planning and Asian Institute of Tourism, makes this observation: “I think the ECQ showed that active transport is doable in Metro Manila if there are few motorized vehicles on the road. The ECQ really brought back the road space for people. Active transport (biking and walking) is only doable if we have enough road spaces that are connected, safe, and green shared with pedestrians and cyclists. Aside from the hard infrastructure that includes people-friendly designs, the soft infrastructure should be there. This means building the culture where motorists respect pedestrians and cyclists like what we see in most developed countries. This would mean embedding prioritizing transport ethics in our educational and motor vehicle registration systems.”

Bike and pedestrian paths in Tsukuba, Japan (photo by Caryn Santillan)

Bike and pedestrian paths in Tsukuba, Japan (photo by Caryn Santillan)

Parked bikes in Amsterdam, Netherlands (photo by Johan Marten)

Parked bikes in Amsterdam, Netherlands (photo by Johan Marten)

How other countries do it

During the quarantine, biking and walking for most people was a novelty. But in other countries, such forms of active transport have always been the norm.

Caryn, who lived in Japan for more than a decade, shares that Tokyo train stations provide overnight parking lots for bicycles so employees could bike from the station to their offices in the morning. “Active transport is very much integrated into their way of life. Very early on, kids are taught to walk to school. They were allowed to use a bicycle to commute when they were old enough. Some bicycles are fitted with attachments for transporting one to two preschoolers, or have baskets for groceries. The bikes have safety features, and need to be registered at the local ward office.”

For seven years, Aloy lived in the Netherlands, where active transport is the default lifestyle with children learning to bike as early as two years old. “Some families even have different kinds of bikes—the everyday, inexpensive one for daily trips to work, errands or visiting friends; and the fancier, sturdier bikes for long-distance weekend trips. There are cargo bikes for carrying your little ones, and e-bikes for older members whose knees are getting weaker.” Because of this, rush hour in the Netherlands looks a lot different from Manila’s carmageddon. “Rush hour in the Netherlands is a swarm of bikes. Bike infrastructure is everywhere. In any party or gathering, I’m guessing that more than 80% of the people came in bikes.”

Caryn in Tokyo, Japan

Caryn in Tokyo, Japan

But in both Japan and the Netherlands, bikes are not the only kings of the road. In Japan, non-bikers like Caryn find it a breeze to walk. “Since most sidewalks are wide and clean, walking in Tokyo wasn’t a hardship—even in heels! When we moved to Tsukuba, which is about an hour away from Tokyo on the express train, I usually walked. It takes around 20 minutes for me and my kids to walk to the city center, but the pedestrian and bike paths are clean and very picturesque.”

Aloy and Bram rode a cargo bike during their 2011 wedding in Netherlands

Aloy and Bram rode a cargo bike during their 2011 wedding in Netherlands

Aloy shares how the Dutch view walking, not just a means to get somewhere, but also a leisurely social activity. “It helps that there are so many parks. I feel that Dutch cities disincentivize car ownership by keeping roads small, maintaining high taxes on cars, taxis and parking fees, and maintaining bike paths with real barriers and bike stoplights.”

Aside from enabling Filipinos to easily clock in the recommended daily ten thousand steps to maintain good health, active transport also allows commuters greater mobility amid the pandemic. “It is the only means for us to really practice social distancing,” Guillen shares. “Walking is the very first mode of mobility that we could really control. Next is cycling, considered an advanced form of walking. If we have a really good walkway or cycling path infrastructure and space, we can easily estimate if we are two meters away from the others.”

Beyond walking and cycling

Aside from active transport, Guillen acknowledges the need for community public transportation that’s both safe and eco-friendly during the pandemic. “Other forms of public transportation would be busses and trains—as long as the social distancing and related health protocols are enforced. For short-distance trips, single-passenger pedicabs and tricycles are an option. However, it is important to note that the old jeepney does not really meet the public transport utility vehicle design standards. The government’s PUV(Public Utility Vehicle) modernization goal, if I understood it correctly, is to really update in terms of design and make the service meet service-level standards. With the pandemic, design and service should now consider social distancing and related health protocols.”

Even beyond the pandemic, Caryn wishes that the Philippine public transport will be a great equalizer like in Japan. “Train passengers are a mix of teenagers, suited businessmen, mommies pushing baby strollers, kimono-clad old ladies, and women in formal evening wear and fur coats,” recalls Caryn. “There are facilities for the disabled—elevators for wheelchairs, tactile paving, braille signs, and audio announcements (in different languages) for the visually impaired. And I greatly admire the pride instilled in their public transport employees. They all know they are part of an important system that helps the city run. They do their job competently and treat passengers respectfully.”

Aloy describes the Netherlands’ public transport system as a “well-oiled machine. When it falls out of schedule with a delayed train, you can hear the deep, deep disappointment rumbling through the crowd, because they are so used to efficiency. I was once on a train where the conductor apologized over the public system that we were arriving five minutes early at the destination.”

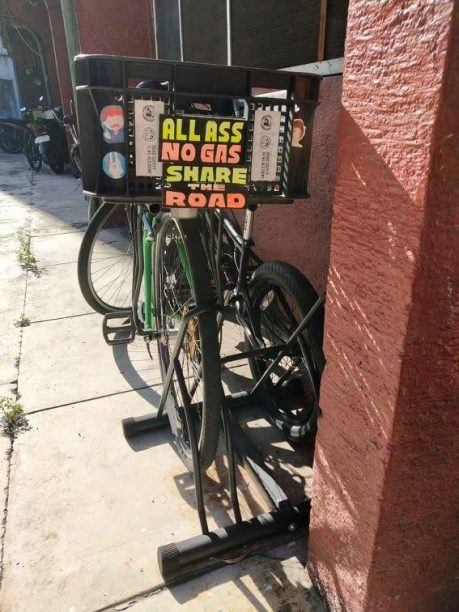

Bike placards (photo by Agay Llanera)

Bike placards (photo by Agay Llanera)

Wishlist for Manila’s public transportation

There is no doubt that the surge of private vehicles in Manila’s roads compound traffic. But why are urban Filipinos so car-centric? Guillen explains, “I think this a product of our long history where building highways was prioritized over the rails, as well as the culture that somehow equate car with economic development. Advertisements to market new vehicles could also play a role. Moreover, there is also the sad reality that public transport and options for active mobility are quite limited. To improve the existing public transport system, there should be enough supply during peak hours and off-peak hours. The system should also consider the active transport component of the whole mobility experience.”

A volunteer assisting bikers during the pandemic (Photo by Jire Carreon)

A volunteer assisting bikers during the pandemic (Photo by Jire Carreon)

Aside from proper bus stops that are strictly followed, Caryn hopes for more waiting areas for commuters, including persons with disabilities (PWDs). “Imagine waiting for a bus under the midday heat or while it’s raining! Also, now that more people are using bicycles, bicycle theft has become a big issue. Establishments should provide secure parking racks— and wider, safer, well-lit sidewalks please, with no vendors taking up the space where people ought to pass. Most of all, I wish we would follow through with urban transport plans despite the changes in administration.”

Aloy wishes for a public transport system that allows commuters to enjoy their travel. “I try to imagine what commuting looks like to a 3-year-old— all 95 centimeters— and it must be frightening. As sociable as we Filipinos are, living in Metro Manila has not made it easy to meet up with friends. If I wanted to enjoy an after-work dinner with a small circle of friends, very few would agree to make it. The city and its transport system simply don’t allow for those connections to be nurtured.”

For Guillen, a country’s public transport system reflects the values of its government and its people. “A country with an exemplary public transportation system means it is a country that truly cares, prioritizing people’s inclusive mobility in the overall system. It is a truly democratic country that provides options to its people on choosing one that truly meets the environment, climate change, and health concerns.”

Chie Roman describes herself as a “rookie pickler”.

Chie Roman describes herself as a “rookie pickler”.

Annette Ferrer is a self-confessed “food nerd”.

Annette Ferrer is a self-confessed “food nerd”.

At the start of the Luzon-wide community quarantine last March brought about the COVID-19 pandemic, rumors of the government implementing a total lockdown surfaced. In response, many Filipinos flocked to wet markets and grocery stores to secure their food supply. The result? Long and snaking lines of buyers, as well as cleaned-out shelves and stalls as food deliveries from companies and the provinces were delayed by stringent checkpoints.

But the very act of going out to contend with the panic-buying crowd was already a great risk, potentially exposing more people to the deadly virus. The key then was to limit the movement of household members—something that Chie Roman, a mom, found essential since her family shared their apartment building with many other households, including her brother and his family, and even a three-month old. One of the solutions she came up with was pickling.

“My husband and I made it a goal to eat vegetables or fruits every day,” she says. “We couldn’t possibly eat canned food all throughout the ECQ (Enhanced Community Quarantine), so we decided to make pickled vegetables.” Chie’s husband took advantage of his twice-a-month trip to the grocery store or wet market by buying a lot of vegetables, which Chie either froze or pickled. “It’s a good life skill for the kids to learn,” she adds. “It teaches them that food doesn’t always come from the sup.

For Annette Ferrer, a self-confessed “food nerd”, pickling is a natural outlet for her culinary passion. “In my twenties, I taught myself how to cook because I planned on living on my own. Fermentation, dehydration, and all my other kitchen pursuits flow from that desire to be independent and self-sufficient. Very early in the lockdown, I felt very lucky and amazed to have been cultivating this passion for food because now is the time that it will really become handy—a survival tool, not only for the body, but also for the mind.”

Pickling 101

Pickling has been around for thousands of years, likely originating in India, where evidence of pickled cucumbers and mangoes dating back to 2400 BC has been discovered. The method was used to preserve food, and to give it added texture and flavor. Pickling usually involves brine (salt and water solution) or vinegar. While vinegar prevents the growth of bacteria that spoils food, brine prevents spoilage due to oxygen exposure. After a few days, the brine acidifies with the help of good bacteria.

In the Philippines, traditional fermentation in earthen jars has led to a variety of well-loved fare, such as bagoong (fermented shrimp paste), lambanog (palm liquor) and atsara (fermented green papaya, carrots and shallots). To make pickled foods more flavorful, the fermenting liquid is usually seasoned with garlic, ginger, red onions and peppers.

Pickling journey

Chie has always dabbled with making kimchi, but only regularly pickled vegetables during the quarantine. Aside from ampalaya (bitter gourd) and young ginger, her family’s favorite is pickled singkamas (turnip). “My first batch of pickled singkamas turned out better than I expected,” she recalls. “It was crunchy, salty and sweet at the same time. I put a sliver of ginger in each jar. We pair it with anything inihaw (grilled) or fried, but it can also be eaten as a snack.”

Pickled singkamas

Pickled singkamas

Meanwhile, Annette’s adventurous palate spurred her on to make variations of kimchi—from the usual cabbage to the more unusual combos of apple-radish and kalabasa-sayote (squash-chayote). “Apple-radish kimchi is my favorite! It’s crunchy and sweet. The kalabasa-sayote is creamy and has a nice bite to it.” She also loves fermenting chilis, spicing them with ginger and turmeric, and the more exotic cinnamon and cardamom. “The chilis are great as a sauce. I don’t need to buy hot sauce anymore. After blending and straining my chili sauces, I fry up the pulp and make another sauce—like the chili-garlic you put on siomai, but with a different flavor. The last one I made had apples and raisins in it.”

Apple-radish-carrot kimchi

Apple-radish-carrot kimchi

Pickling in the time of a pandemic

Life during a pandemic is rife with uncertainties. For Chie and Annette, pickling is part of the new normal of being self-reliant and thrifty. Chie explains, “We’ve been able to save money and cut down on waste. The vegetable peels, seeds and scraps, we either put in the compost bin or plant in containers.”

Chie’s ginger harvest

Chie’s ginger harvest

Though Annette is fully aware of how fermentation is an economical and practical means of preserving food, the process also fulfills her on various levels. “It is creative, intellectual, manual, but also nourishing, and a part of resistance and independence. If we only know how to buy our food, we are only consumers in the capitalist system—and there is only ‘one taste’ to things such as sinigang, kare-kare, pancit canton because we eat them from commercial spice mixes. But by making our own food, we are more in touch with our history and culture. Sandor Katz, a fermentation revivalist, says that fermenting is resistance to the idea that bacteria is bad, that everything should be sterile. Fermentation gets us in touch with worlds that are not just ours—the world of yeasts and bacteria.”

Annette pickles sayote ang goji berry (center); singkamas and carrot (right)

Annette pickles sayote ang goji berry (center); singkamas and carrot (right)

Never-ending gastronomical journey

Both women’s forays into food preparation don’t end with pickling. Chie’s roof deck has become a haven for her container gardens of herbs and vegetables. She also makes homemade yogurt, her family’s source of probiotics that promote digestive health.

Chie dries her basil

Annette has taken on making her own vinegar from fruits such as pineapple, banana, orange and jackfruit. Recently, she’d bought a dehydrator and has since been making dried fruits. “They’re like candy! During the ECQ, we would go to the market once every two weeks. Sometimes, we try to stretch it to three weeks. So you can imagine how the fruits needed to be consumed first. By week two or three, we don’t have any more.”

(clockwise) Annette’s dried mango; pineapple; apple; dragonfruit; dayap

(clockwise) Annette’s dried mango; pineapple; apple; dragonfruit; dayap

As for those who want to try pickling, Chie advises, “The most important tip is to make sure you pick the freshest vegetables. Different vinegars yield different tastes. I’ve used rice wine vinegar, apple cider and good old cane vinegar. I still have lot to learn. I am a rookie pickler and Google is my friend.”

Annette encourages beginners to follow their palate. “Start with something you like to eat— if it is kimchi or vinegar, or pickles, or hot sauce! That first success is so encouraging, so aim for simple projects first, then expand.”

4 cloves garlic, minced Half inch ginger, chopped 1 large Fuji apple or 2 small, chopped into 3/4 inch cubes 1 large daikon radish, chopped into 3/4 inch cubes 1 medium carrot, chopped into 3/4 inch cubes 1 bunch spring onions, sliced into 1.5-inch length 1 heaping tablespoon of rock or sea salt Fish sauce to taste 1-4 tablespoons gojugaru or Korean red pepper flakes

- In a large bowl, combine the apple, carrot, radish, salt, garlic, and ginger. Let it sit for about 15 minutes.

- Mix ingredients to check if they have released their juices. Add fish sauce and more salt if necessary.

- Add in 1-4 tablespoons of gojugaru or to taste, depending on how spicy you like it.

- Add in spring onions and stir everything to combine well.

- Transfer the fresh kimchi into a clean glass jar with a non-metallic lid. With a large spoon or with your fist, pack down the kimchi so that the vegetables are submerged in their own juices. Leave about an inch of space at the top of the container for fermentation.

- Cover with the lid and set aside at room temperature overnight or for 2-3 days, depending on how sour you want your kimchi to be.

- When the kimchi has arrived at the level our sourness you enjoy, transfer into the fridge to slow down the fermentation process.

Weather is no longer a mundane topic people use to make small talk. Nowadays, news about the weather makes Filipinos straighten up and listen because of the countless ways it impacts their lives. This is precisely what inspires PAGASA Weather Specialist Ariel Rojas when he delivers the forecast—with his eyes alert and his hand sweeping across the graphics-generated Philippine map.

“I’ve always been curious about the weather. I was born and raised in Bicol where it always rains and tropical cyclones always visit,” he shares. His journey toward weather forecasting began when he took up B.S. Meteorology in UP Diliman’s graduate school under a PAGASA scholarship. In 2017, he began working in PAGASA, and had since been trained here and abroad, allowing him to gain new knowledge and techniques in weather forecasting.

Rojas regularly appears on Panahon TV to deliver the weather forecast, but with Panahon TV’s first free webinar, Intro to Philippine Weather, he’ll get to share more of his knowledge. We sat down with him to delve deeper into his childhood passion.

What are your current duties in PAGASA?

My main duties include analyzing weather data, maps, and models to formulate weather forecasts, and presenting the forecast product to the public through PAGASA’s online platforms and interviews with media outlets. I also conduct lectures on weather forecasting or other weather-related topics to media practitioners and students.

Do you think it’s important for Filipinos to have basic weather knowledge?

Yes, it is! The Philippines is the most tropical cyclone-visited country in the world! That alone should be enough reason. We are also an agricultural nation so many farmers depend on the rain. Our economic, agricultural, and other daily activities are informed by the state of the atmosphere so basic weather knowledge is a must for everyone.

If there’s one thing you’d like every Filipino to know about weather forecasting, what would it be?

That weather presenting is only the tip of the iceberg. Forecasters analyze weather data, maps, and models to come up with the final forecast and all of these take time. Tropical cyclone events require more time and harder analyses.

How do you feel about being part of the Panahon TV webinars?

I always look forward to joining Panahon TV activities because they’re fun and I learn a lot. I feel honored to have been invited to take part in this webinar. I am also trying to further hone my communication skills so this would be a great platform for that.

What do you hope participants will take away from your workshop?

I hope that they will carry with them whatever little nugget of weather knowledge they can take away from the workshop. We basically experience the same weather patterns every year so just knowing when these patterns change can greatly help them in their decision-making, even the most mundane ones like choosing which clothes to wear or when to book an out of town trip.

To join Panahon TV’s free webinar Intro to Philippine Weather with Ariel Rojas on June 2, 2020 at 2:00 p.m., register at https://bit.ly/3d70vTk .

On the first day of Luzon’s Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) last March 16, the world—or at least this part of the world—seemed to have come to a standstill. No motorcycles roared on the streets, allowing silence to breathe in spaces that had always teemed with noise and activity. Suddenly, staying away from the people dearest to us became a supreme act of love.

Though essential-goods stores such as wet markets, supermarkets, pharmacies, and some eateries remained open, a lot of businesses closed shop to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Even the ever-present media wasn’t spared by the pandemic; some channels put production on hold, and aired only replays.

Despite the health crisis, Ube Media’s Panahon TV—committed to its advocacy of spreading accurate information, not only on the weather, but also on disaster resiliency, climate change, agriculture and most importantly, health—continued to air original content.

How they did it

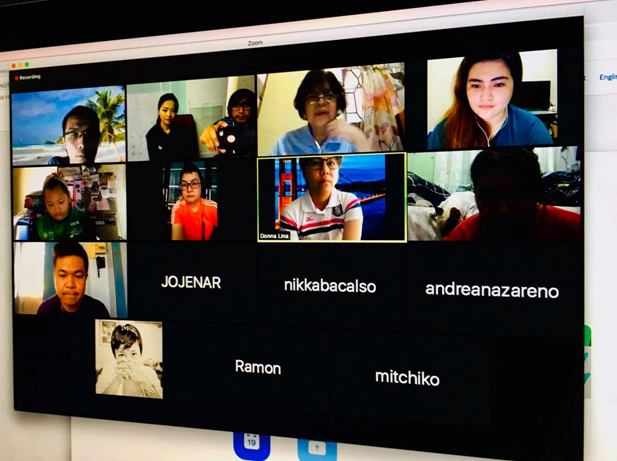

Executive Producer Donna Lina explained that a plan was mapped out with the team to figure out the most feasible way of operating the studio with the least amount of people. “It helped that we are a show that deals with the weather and DRR (Disaster Risk Reduction), so we’ve always prepared for the worst-case scenario. It would be such a disservice to all of us if we weren’t prepared. Part of our training in Panahon TV is to check outside threats.”

To reduce risks, the show allowed a rotating team of only five people in the studio housed inside the Quezon City building of the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA). While the rest of Panahon TV’s staff worked from home, the studio team included a reporter, producer, cameraman, web administrator, and video editor. Content Head George Gamayo added, “The production staff is fetched and sent to their homes using our media van. The vehicle is disinfected after service. There are weekly schedules for office disinfection. The exhaust fan is turned on during and after disinfection to reduce the risk brought about by aerosols.”

Shooting, especially in the field, is the backbone of socially-oriented TV shows like Panahon TV. But because of the ECQ, the team needed to be creative in sourcing videos. Since the ECQ, all interviews have been conducted through video-conferencing platforms, while other footage are crowd-sourced. “We’ve been experimenting with content in digital media,” Gamayo explained. “During the ECQ, we developed #LockdownDiaries, a vlog-type segment co-produced with overseas Filipinos sharing their hopeful stories amidst the pandemic. Another one is May Say ang Kids, which shows how children understand the virus and the pandemic.” Both these shows have garnered thousands of views on Panahon TV’s Facebook page—proof that the stories resonated with viewers.

Daily Routine

The production team stays in the studio for two weeks before being replaced by the next batch. Supervising Producer Fatima Caberos shares their routine: “We wake up at 3 am to prepare for the live broadcast. We air at 5 to 6 a.m. on Cignal, then at 6 to 6:30 a.m. on Life TV. After that, our technical team prepares breakfast, while our reporter updates our social media, and our graphic artist sends layouts to mailers and our (broadsheet) print partners. After eating, we clean the studio and take a quick nap. We have lunch then resume working. Then we air at 6 p.m. on Cignal. We eat dinner, clean up, take a bath and sleep.”

Lina makes sure they are provided with ample food—and water delivered to the studio from the cargo house of Air21, part of the Lina Group of Companies. Usually, Caberos buys groceries with another motorcycle-driving team member. Before entering the studio, they take a quick bath and sanitize the items they bought. To boost their immune system, they take morning walks in the PAGASA parking lot for their dose of Vitamin D.

In it for the long haul

Because the pandemic isn’t going away anytime soon, Lina keeps communication lines open to make sure that despite the absence of face-to-face communication, she can check on how her employees are feeling. “Ensuring that people continue to have a positive working environment is something we strive to have. This, we do by having regular general assemblies and collaboration. It’s a great deal of teamwork and doing the ‘homework.’ In Filipino, ‘yung lahat, tulung-tulong.” (Everyone helps out.)

Caberos agrees. “What I learned from this is that sometimes, it’s a matter of sacrifice and showing concern. We’re grateful that we can still earn. I’m very proud of our team because limited resources don’t keep us from producing and sharing good stories that help people.”

Facing the Future

Though Panahon TV’s current setup seems to be working, it is still far from the ideal. Gamayo elaborates, “Those who are working from home have their share of disruptions, such as power outages and poor internet connection, which delay our workflow. And since we’re doing TV production, we rely on online platforms to send and receive large video files, which consumes too much of our time.”

Emotional and mental health are also at risk, which may lower productivity. “We understand that people cannot be enthusiastic and productive all the time,” Gamayo adds. “Thus, we really have to be very careful of how we communicate with our colleagues.”

For Lina, the whole thing is a learning process. “I’m learning more about resource and energy management, about the capacity of everyone to help each other. I’ve learned to think faster to find solutions, and to select only the essential activities for the time being.”

Even now that Metro Manila has transitioned into Modified ECQ, Lina remains vigilant, maintaining stringent safety precautions in the workplace. “We will have to take extra measures and evolve to the new normal. Only until there’s a vaccine and there are zero cases can we really relax.”

Agay Llanera – Head writer, Panahon TV

When there’s a big typhoon in the Philippines, we follow the protocol on class and work cancellations. This protocol has been built on experience since around 20 typhoons enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility every year.

The same can’t be said for the present COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) outbreak. The closest the world knows of such a health crisis is SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), which, according to the World Health Organization, produced more than 8,000 cases and 774 deaths from November 2002 to July 2003. SARS-affected countries such as Taiwan and Hong Kong learned the hard way, but are now better prepared for a similar outbreak.

COVID-19 is highly infectious, affects people with compromised health, and is arguably bigger in scope. For us here in the Philippines, there’s no precedent. The cholera outbreaks that pepper our history are probably the closest we’ve experienced to this recent crisis. More than ever, we need the input of sociologists, anthropologists, and psychologists on how humans have behaved and should behave during these events.

Everyone wants things to go back to normal. But for now, we accept things just as they are. Have you ever imagined going through so many temperature checks before entering an establishment? We want to live as normal as possible without disrupting the economy. But the economy has already been disrupted due to massive fear, and may take a turn for the worse—or, we hope, for the better.

In the meantime, we can do the following: 1) Educate ourselves with proper information, 2) Exercise proper hygiene, and 3) Prepare our resources.

Take time to draft your SHTF plan. And in case S doesn’t Hit the Fan then no problem, you can breathe easy. The time you spent on preparing isn’t wasted time. Because the more ready you are, the better it is for all of us.

Donna May Lina is Executive Producer of Panahon.TV, a weather, climate change, and preparedness program, which airs daily at 5:00 am on OnePH, Cignal. She spoke at the 3rd Asian Broadcasting Union (ABU) Media Summit on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2017. She also attended and covered the United Nations World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai, Japan in 2015.

- What is coronavirus?

The coronavirus is a type of virus that causes respiratory illness in animals and humans. It is zoonotic, meaning it can be transmitted between animals and humans. The virus was first discovered during the 1960s, and was called coronavirus because of its crown-shaped structure.

As of now, there are seven types of the coronavirus that can infect humans. They range from the common cold to more severe diseases, such as the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV), and its latest strain, the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19).

MERS-CoV, discovered in Saudi Arabia last 2012, resulted in 858 deaths. According to scientists, this coronavirus came from camels and has flu-like symptoms. Meanwhile, SARS began in China in 2002. It was reported to have come from a civet cat, and has 8,000 confirmed cases, killing almost 800.

On January 9, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a new strain of coronavirus, associated with an outbreak of pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Last February 11, 2020 it was renamed as the Coronavirus Disease-2019 COVID-19.

- Is COVID-19 deadly?

Just like MERS-CoV and SARS, the COVID-19 is deadly. The moment one gets infected, the virus spreads immediately to the lower respiratory tract, including the lungs. This type of coronavirus may cause severe pneumonia in 24 hours, and it cannot be cured by antibiotics.

- What are the symptoms of COVID-19?

Its respiratory symptoms include fever, cough, shortness of breath and other breathing difficulties. However, there are cases of the coronavirus disease that are asymptomatic or display no symptoms. It takes around 14 days before the symptoms appear.

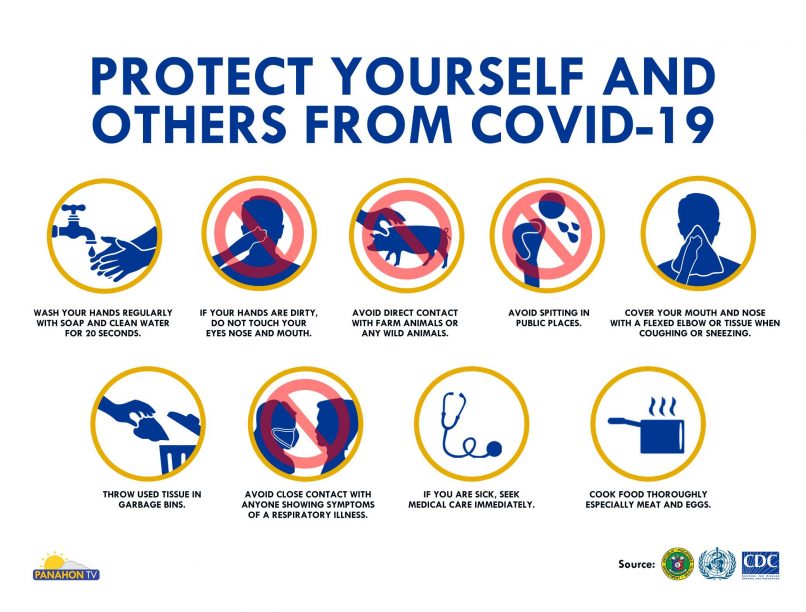

- How can you protect yourself from this virus?

According to the World Health Organization, here are the ways to prevent yourself and others from getting the COVID-19:

- Wash your hands regularly with soap and clean water for 20 seconds.

- If your hands are dirty, do not touch your eyes nose and mouth.

- Avoid direct contact with farm animals or any wild animals.

- Avoid spitting in public places.

- Cover your mouth and nose with a flexed elbow or tissue when coughing or sneezing.

- Throw used tissue in garbage bins.

- Avoid close contact with anyone showing symptoms of a respiratory illness.

- If you are sick, seek medical care immediately.

- Cook food thoroughly especially meat and eggs.

- What should you do if you have a scheduled travel abroad?

- If you are sick, avoid traveling.

- If you’re sick, seek medical care immediately and share your recent travel history.

- If you are wearing a face mask, make sure to cover mouth and nose. Avoid touching mask once it’s worn.

- Discard the single-use mask after each use and wash hands immediately.

- Avoid close contact and travel with sick animals.

- Make sure to eat well-cooked food.

- How can you cope if you’re stuck abroad and can’t go home?

- Keep in touch with your family.

- Maintain healthy lifestyle, including proper diet, sleep and exercise.

- Don’t believe everything that’s posted on social media. Get the facts. Always check reliable sources of information about this disease.

If you need more information, please check these sources:

- Department of Health – https://www.doh.gov.ph/

- World Health Organization – https://www.who.int/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/

The leap year only occurs every four years, which means that the last time we had a 366-day year was in 2016. But why do we need to have the 29th of February every so often?

Leap year and its occurrence

According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), leap years occur to match our calendar year to the solar year—the amount of time it takes for Earth to orbit the Sun.

Normally, the Earth takes 365 days and 6 hours to go around the Sun, while it takes 24 hours and 1 day for the Earth to rotate on its axis. Since a year on our planet is not an exact number, most of our years are rounded off to 365. But the thing is, the remaining hours don’t just evaporate into thin air. To take these into account, we need to add one day to the calendar, leading to the existence of the leap year.

Father of Leap Year

Julius Caesar was named as the Father of Leap Year way back in 45 B.C. He adopted the Egyptians’ 365-day year and established the leap year system to correct the calendar every four years.

Other planets have leap years

Just like here on Earth, leap years occur on other planets, too. Mars, for example, has more leap years than regular years. NASA says that a year on Mars is composed of 688 days. However, it takes 668.6 days for Mars to go around the Sun. To compensate and help the calendar catch up, days must be added.

On myths and practices

Around the world, several traditions are observed during the 29th of February. In Ireland, women propose to men on leap days. This tradition was taken to Scotland by Irish monks in 1288. Back then, the Scots passed a law, which allowed women to propose marriage. Any man who declined the proposal used to pay a fine.

Others believe that the leap year brings bad luck. Some of the notable events that happened during a leap year include the Titanic sinking in 1912 and Ancient Rome burning in 64 A.D.

Despite this, leap years bring a sense of wonder and delight, especially for those born on leap days, who only get to celebrate their exact birthdays every four years.

According to the UN Environment Program, every year, an estimated 11.2 billion tons of solid waste are collected worldwide. The amount of waste doubles during holidays, long weekends and special occasions, such as Valentine’s day. So why not try these gift ideas for a zero-waste valentine?

Potted plants. Instead of giving flowers, consider giving plants. A potted plant lasts longer than a bouquet of flowers. Living plants help the environment since they release oxygen, absorb carbon dioxide, serves as habitat and food for wildlife, and help regulate the water cycle.

DIY gifts. Making gifts may consume a lot of time, but this allows you to get creative, resulting in more personalized items. Consider the hobbies and preferences of the receiver. Whether it’s a crocheted decor, a painted portrait, a hand-written letter, or home-baked cookies, your giftees will appreciate the effort you’ve poured into your gifts.

The gift of experience. To avoid unnecessary waste that usually starts with unnecessary shopping, hop on to the “gift of experience” trend. Go and take your date to a movie, play or an amusement park. Or better yet, shower your special someone with acts of services, such as cooking meals, cleaning the house, or giving a massage. After all, experiences tend to be remembered more than material things.

Go for locally-grown items. Support local crafters and workers by purchasing items sourced and made locally. This helps in cutting down fuel consumption and air pollution created by items delivered through overseas planes and long-truck trips. Also, skip the plastic wrap!

Remember, it is not necessary to spend huge amounts of money to celebrate Valentine’s Day. Show the environment some love, too!

After the Quadrantids Meteor Shower last January 4, the skies will once again be illuminated by another major astronomical event—the Penumbral Lunar Eclipse.

Eclipses come in pairs

A solar eclipse is always paired with a lunar eclipse. A solar eclipse only happens during the new moon, while a lunar eclipse occurs during the full moon. For an eclipse to occur, the new and full moons have to take place within the eclipse season, wherein the Earth, Sun, and Moon are perfectly aligned. This happens twice a year, about six months apart.

What is a Penumbral Lunar Eclipse?

On January 11, 2020 at 1:07 a.m., the Penumbral Lunar Eclipse will be visible in the country. It occurs whenever the Earth passes between the Moon and the Sun, blocking out sunlight and casting a shadow on the Moon’s surface.

Unlike other types of eclipses, a Penumbral Lunar Eclipse is more subtle and much more difficult to observe. According to Fred Espenak, an American Astrophysicist, about 35% of all eclipses are penumbral. Another 30% are partial eclipses, while the remaining 35% are total eclipses of the moon.

Where will the Penumbral Eclipse be visible?

The eclipse will be visible in Africa, Oceania, Asia, Europe, and Northern America.

In Manila, the Penumbral Lunar Eclipse starts at 1:07 a.m., reaching its peak at 3:11 a.m. and ending at 5:12 a.m. The next eclipse for the year will be visible on June 6.