Among the total number of overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) pegged at 2.2 million by the Philippine Statistics Authority in 2019, over 300,000 have so far been repatriated by the Department of Foreign Affairs because of pandemic-disrupted economies. Though this was deemed as the “biggest repatriation effort in the history of the DFA and of the Philippines” by Foreign Affairs Undersecretary for Migrant Workers’ Affairs Sarah Lou Arriola, the numbers indicate that majority of OFWs still remain in other countries.

Recent events have created stress for OFWs, who have their own struggles even without the health crisis. Psychologist Roselle G. Teodosio, owner of IntegraVita Wellness Center, explains that the OFWs’ primary source of stress is being away from their families. “The OFWs usually worry about the families they leave behind. This is especially true for those who have spouses and children. Another stressor is the culture shock or how to cope with the daily grind of living in a foreign land. The language barrier is a major stressor for OFWs aside from adapting to the new culture.” Financial obligations also create pressure as families and relatives tend to think OFWs make lot of money. “The family and relatives do not realize the sacrifices and hardships the OFW makes to be able to send money. Another stressor is their employers and co-workers. An abusive employer is not uncommon, and there may be multiracial co-workers. Different cultures tend to clash and lead to conflicts at the workplace.”

With the pandemic affecting economies and causing people to lose jobs, OFWs may be overwhelmed by multiple pressing problems. “There is fear, not only for the OFWs’ health, but also for the families dependent on them. Knowing that there is a greater risk for their families back home, there will be greater pressure on OFWs to retain their jobs,” says Teodosio. “There is the fear of a family member contracting the virus. The inability to be at the bedside of the sick family member will weigh heavily on the OFW. Also, the fear for one’s own health in a foreign land can be daunting. The OFW has to stay strong and not show the family back home that he is really scared since he thinks this will add to his family’s worries.”

As if these complications weren’t enough, now the holiday factor is thrown into the stressful mix. Because of the pandemic, OFWs who normally go home at this time to celebrate Chrismas with their families are forced to stay in their countries of employment. “Even the families of the OFWs feel the fear of their loved ones contracting the virus abroad or if they force themselves to come home. Another concern is if they go home, will they be able to go back to their jobs? So to make sure that there is a semblance of the security of tenure, then the OFW will remain where he is and not try to go back. The risk of getting infected is much higher if the OFW will try to come home,” shares Teodosio.

Christmas away from Family

Agnes, who has been working in Taipei for almost 5 years, comes home once a year during the holiday season. Like most Filipinos, she regards Christmas as the time to be with family. “My siblings and I are all working professionals, and Christmas is the best time to be in the same place altogether, as we usually take a two-week vacation leave from work. I spend most of my December with family, and since we’ve had a baby in the family—my younger brother’s— it’s been a lot more fun and special.”

Agnes admits that this is her second time to skip spending Christmas with her family. “Last year, I had to go to Italy for the wake of my fiance’s mom. I didn’t feel the impact of not being with my family on this important holiday because I was in a different country, and also needed to support my fiance and pay my respects. But this year, I’m definitely feeling the impact.”

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Husband-and-wife OFWs Armie and Boyet in Qatar

Because of the nature of their jobs, Armie and Boyet who have been working in Qatar for 9 years don’t really get to go home during the holiday season. “That’s a busy time in the office,” shares Armie. “So we go home usually in April or May. But we didn’t get to do that this year because of the pandemic. So we thought we’d go home in December for a change—but that plan fell through as well.”

Still, spending Christmas away from her children and her 80-year-old mom for almost a decade has taken a toll on Armie. “It gets sadder each year. Sometimes, I hear a piece of music that reminds me of home, and already, I get emotional. There’s this deep longing to have our family together. When my husband and I first arrived here, we missed our family, but there was the novelty of discovering a new place and culture. Now, we just simply miss our family.”

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Armie with her daughter and her 80-year-old mom

Increased Anxiety and Worry

Affirming what Teodosio mentioned, Agnes confesses the stress and anxiety she experiences at work is compounded by the pandemic. “I know I have the choice to not tune in to the news, but I always worry about the effects of the government’s ineptitude on my family and loved ones. I sometimes think I may be getting too emotional and overreacting, but I’ve been feeling like this for quite a while. It’s hard to be in a different country with no support system.”

Even if she’s able to go home, Agnes would rather stay in Taiwan for several reasons. “Although my host country has handled the pandemic well, no one knows if you’ll be able to contract the virus in transit. I don’t have enough leave credits to do a long-period quarantine, and I certainly don’t want to spend Christmas in quarantine.” Though her family understands her decision, Agnes can’t help getting emotional. “The knowledge that I can’t be with my family on this important holiday is making me feel depressed. We sometimes have video chats and I’ve brought up the topic of missing them a lot especially in these stressful times, and they’ve been supportive to a certain extent. Nevertheless, it’s still a painful decision even if it’s a necessary one.”

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Armie and Boyet with their kids in 2018

Though Armie worries about her family contracting the disease, a temporary setback came in the form of her husband’s 5-month unemployment. “He works in a gym, which shut down during the pandemic. The gym is back in business now, but during those 5 months, I worried about making ends meet. Somehow, we did it by cutting back on expenses.”

November brought Typhoon Ulysses, which submerged their house in Bulacan. “My kids and my mom didn’t have electricity and drinking water for several days. I asked help from friends in the Philippines, who thankfully helped them out. Now, my kids are busy with house repairs.” Though her children are used to Armie and Boyet’s absence, Armie confesses that her heart broke when her husband asked them what else they needed. “My kids replied, ‘You. We need you both. Please come home.”’

Coping this Holiday Season

The combined challenges of the pandemic and the holiday season may be difficult, but they can be conquered. Our interviewees offer these tips:

Stay grounded. “OFWs need to be resilient during these trying times. Focus on the things that they can control such as their thoughts, emotions, reactions and behavior. So in a time of pandemic, they can do their part in keeping safe by following safety protocols,” says Teodosio.

Find a support group. While taking a leave from work to “unplug from the stress,” Agnes is going to meet up with Pinoy friends in Taiwan. “We’re planning to have Noche Buena together and watch the fireworks display on New Year’s Eve.”

Stay healthy. Agnes tries to cope by taking care of herself physically and mentally. She adds, “So when it’s safe to travel, I’ll be in a better state and be able to make up for lost time.” Teodosio advises OFWs to differentiate between good and bad anxiety. “Some anxiety may be productive; this is what makes us wash our hands often and socially distance ourselves from others and keep our masks on,” she explains.

Focus on the present. The OFW needs to take one day at a time. “Excessively worrying about the future for himself or his family can sometimes paralyze a person with fear,” says Teodosio. “Becoming aware and mindful of all his thoughts and feelings can be very helpful in managing these emotions.”

Connect with family. Armie and Boyet make it a point to virtually share the annual Noche Buena with their family. “I plan their meal, take care of the budget, and make sure they decorate the house. When midnight strikes, Boyet and I eat with them via video chat,” shares Armie. Teodosio encourages OFWS to maintain constant communication. “Trying to weigh the pros and cons of coming home can help the OFW and their loved ones in understanding what is more important to them—the health of the OFW or being together during Christmas. Having the patience for one another and thinking of what is best for everyone will help the families cope in these trying times.” Agnes affirms this: “Sometimes I feel helpless, but at least with the chats and messages, there’s still something I can do even if it’s a small thing.”

If you’re anxious or depressed, don’t hesitate to reach out to the following:

- Roselle Teodosio (psychologist) – 09166961223 and 09088761223 or email: selteodosio@gmail.com

- National Center for Mental Health Crisis – 09178998727

- Philippine Mental Health Association – 09175652036

- Philippine Psychiatric Association – 09189424864

Plastic-wrapped nation. Illustrated by sticker artist Zahnina Jayne Rosal ©2020

Nearly everything we use in our daily lives is made of plastic. We start the day by using a plastic toothbrush. To save money, we pack meals in a plastic container. On the way to the office, we pick up coffee in a disposable cup, which sometimes comes with disposable plastic straw. At the office, we attend a meeting that serves water, juice, or soda in PET bottles.

These modern conveniences seem harmless but in abundance, compounded by habitual improper waste disposal, is how the world has found itself nearly suffocated in plastic.

Single-use plastic is everywhere

According to a United Nations environmental report, “Our planet is drowning in plastic pollution. Around the world, one million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute, while up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide every year.” Half of these plastics are manufactured as single-use products, eventually discarded to contribute to the 300 million tonnes of plastic waste and debris the world produces annually.

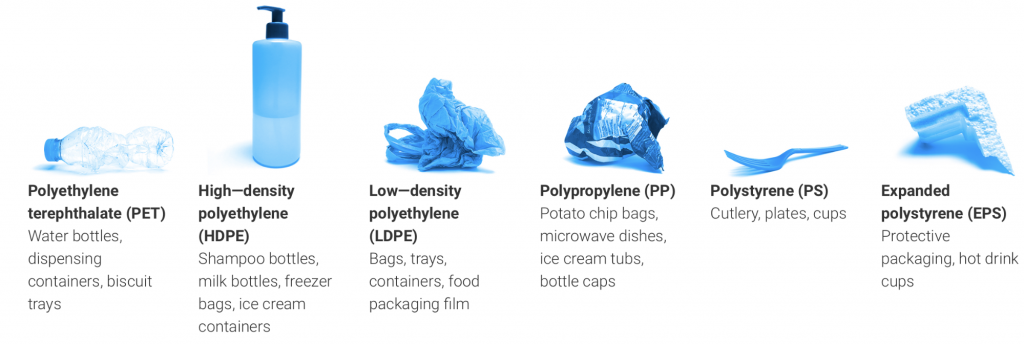

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

These plastic pollutants degrade into smaller fragments—from undetectable microplastic (>5mm) about the size of sesame seeds, to macroplastic (<5mm) large enough to be easily recognized in its original form. These find their way into catchments before being discharged to rivers, seas, beaches, and recently, even in remote, pristine locations like Lake Geneva in Switzerland and Lake Guarda in Italy.

The world is so littered with plastic that a recent study has indicated the presence of small pieces of plastic waste even in the remote mountain ranges of the French Pyrenees. Samples found from the mountains include microplastics likely from single-use plastic packaging from take-out food and PET bottles transported through the air.

The throw-away culture and soft plastics

In the Philippines, soft plastics are the most prevalent plastic litter found in our waters, according to Amy Slack, an environmental consultant who regularly volunteers for Marine Conservation Philippines to work with international movement Break Free From Plastic in Negros Oriental initiative. In her analysis of plastic waste collected during their group’s beach cleans in December 2019, she blogged: “Consistently, the vast majority of the debris we found strewn across the beaches across the Philippines was plastic; a significant amount of that was soft plastics which can’t be recycled – plastic bags, sweet and crisp packets, and single-use soap and detergent sachets. There were some variations though: at one beach, we kept picking up a staggering amount of styrofoam.”

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Though their organization was able to fish out trash and segregate, another road block cropped up. According to Slack, “It became increasingly apparent that part of the problem was the variability of waste management across the municipality of Zamboanguita, in the Negros Oriental province.” Aside from the lack of resources or end-points, many locals have no recycling knowledge at all. This seems to be the case not only in the municipality of Zamboangita, Negros Oriental, but also around the country.

Meanwhile, Czarina Constantino of World Wide Fund for Nature Philippines (WWF), also the national lead for “No Plastics in Nature” Initiative acknowledges this. “Meron ‘pag Luzon, pero ‘pag mga Visayas or Mindanao, Hirap sila. Kasi archipelagic pa rin tayo. Sobrang hirap rin para kulektahin ang mga basura. Sobrang gastos. (There are in Luzon, but they’re scarce in Visayas and Mindanao because our country is archipelagic. It is very challenging to collect garbage. It’s very expensive.)

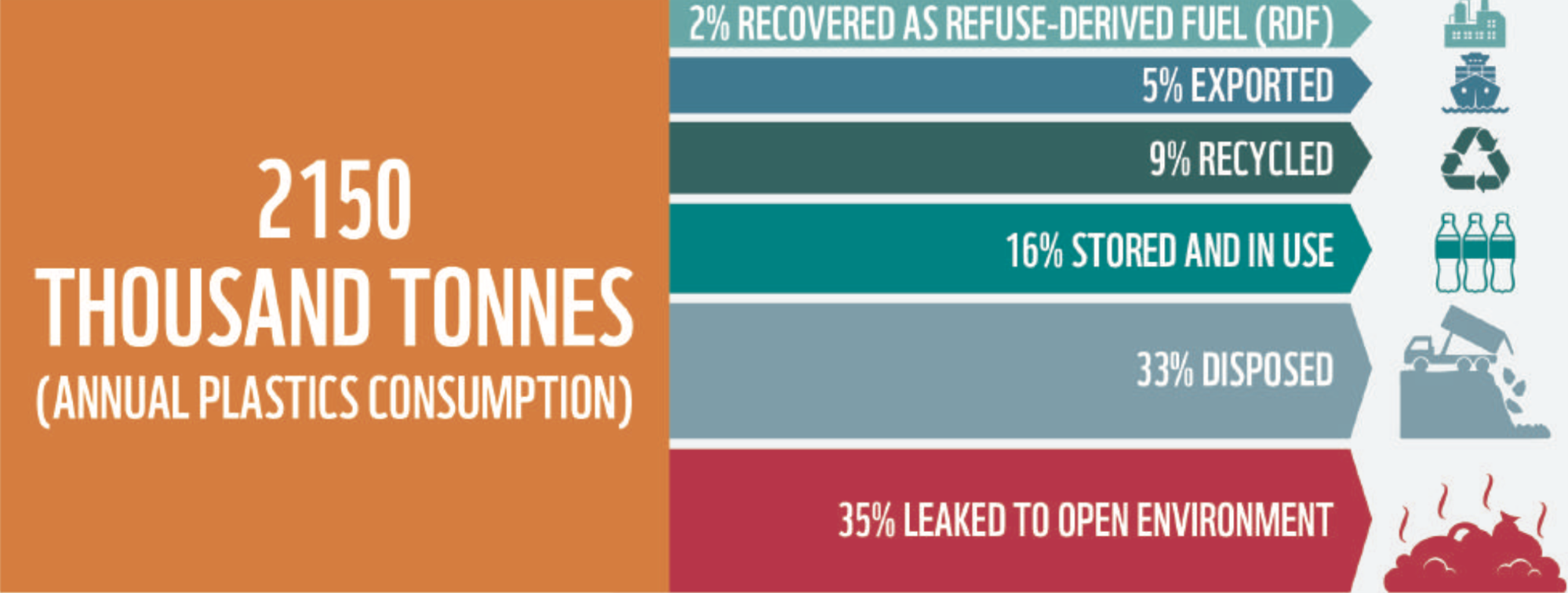

The number of recycling facilities in the country is too limited to accommodate all the plastic waste the country generates, which is about 20 kilograms per person annually, or 2,150,000 tons of plastic waste in 2019, according to the 2020 WWF findings from its recently conducted material flow analysis of plastic packaging waste.

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Sachets, Extended Producers Responsibility and eco-design

Sachets are made of several layers of different types of plastic, which require separation prior to recycling. Some of these layers have very poor recyclability, and with all the mechanical steps required to separate them, it is neither economical nor profitable to recycle sachets. It is decidedly a single-use product, and a good number of case studies suggests it to be the likely culprit to our environment’s plastic woes.

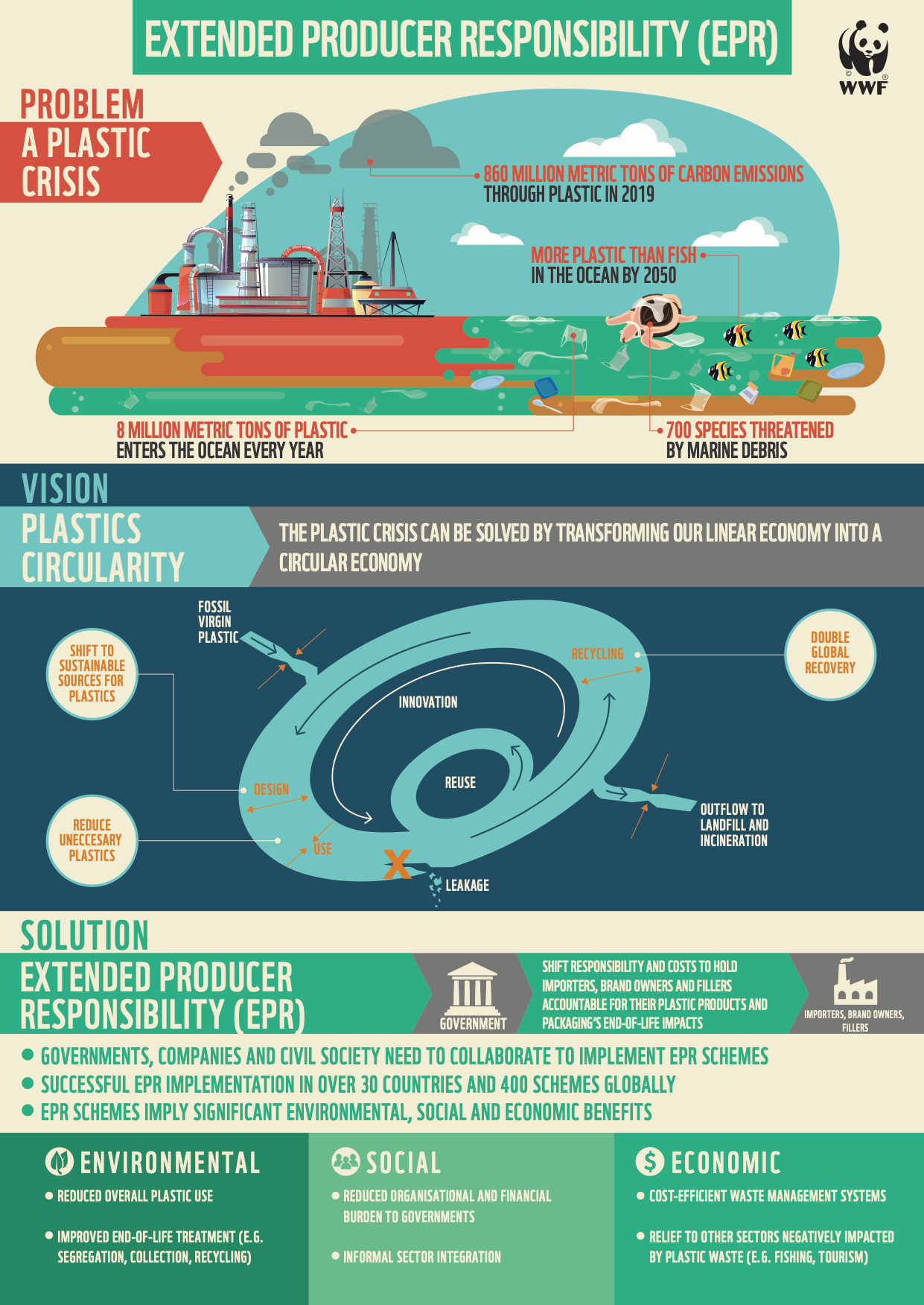

According to the United Nations, the Philippines is one of five countries from which plastic pollution originates before flowing to the rest of the world. To help address this, WWF along with Congress, are working on a legislation that shall compel producers, manufacturers and businesses to be accountable for the waste they put into the market. A scheme, here and abroad, called Extended Producers Responsibilty (EPR), shall bill them ahead for their plastic waste contribution to society. This is expected to encourage stakeholders to redesign their products with recyclability or reusability in mind to avoid exorbitant EPR fees. One of the first effects expected out of EPR is the innovation of eco-friendly plastic products. Other than RA 9003, otherwise known as the Philippine Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, this is by far one of the most aggressive steps taken towards arresting the catastrophic effects of non-recyclable plastics in our environment.

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

Paper or plastic?

It is not enough to opt for paper bags while shopping. This practice potentially harms virgin forests, while reusable bags require 131 uses to qualify them as sustainable. Waste management remains an ideal option—which, unfortunately, local governments find difficult to finance. Constantino relates, “Most recycling facilities WWF has worked with are privately owned. It is also a fact that most machines that local governments own are for composting, and not recycling.”

Though the lack of recycling facilities and accessible recycling programs add to the ongoing plastic crisis, there is simply an overwhelming amount of plastic wastes, which spill out to nature and contribute to flooding issues. In this light, Constantino stresses the importance of household waste management system. “Start with ourselves. Apart from changing yourself, you also have to change the system. Practice segregation. Apart from changing your lifestyle, you have to change the system so you can influence. People can influence systemic changes in their areas.”

Plastic use in the time of pandemic

A recent study conducted in July 2020 by Pew Trusts indicates that at present, 11 million metric tons of plastics enter the oceans annually, which can possibly triple by 2040. Still, Constantino acknowledges there are necessary plastics. “We do not say that let us eliminate all plastics. For WWF, there are necessary plastics. We usually relate them to food safety and health security. If it’s something that would help decrease the food wastes, we’re okay with that.”

However, this projection has not taken into account the pandemic effect on the usage of plastics brought about by food consumption and health security. In the Philippines, our waste management solution is mostly through landfills shared by cities. Presently, the WWF has not received confirmation on whether the lifespan of these landfills will be greatly affected by the increase in plastic consumption these last few months.

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

WWF expects the numbers to rise as a consequence. “While we were conversing with Manila City, ang next nilang problem, mapupuno na raw yung landfill by 2026,” Constantino shares. “That’s pre-COVID, pero ngayon hindi ko alam kung that is still the projection. Recently, there’s really a significant increase of plastic use—lalo na yung mga tao, stay at home, padeliver lahat. Some businesses, dati pwede ka magdala ng resuables, pero ngayon, kinansel muna nila due to health reason daw. Kasi parang nag-shift din yung mga businesses, na dating nag-re-reusables, or dating nag-e-entertain ng reusability, ngayon, parang stop muna natin.’” (While we were conversing with the Manila City government, they shared that their next problem is that the landfill could be filled to capacity by 2026. That’s pre-COVID, but now, I don’t know if that is still the projection. Recently, there has been a significant increase of plastic use. Because people are at home, everything gets delivered. Some businesses used to allow reusables, but these days, that option is cancelled, supposedly due to health reasons. There appears to be a shift among businesses who used to accommodate reusables, or those who used to entertain reusability. But now they’re saying, “Let’s stop for a while.”)

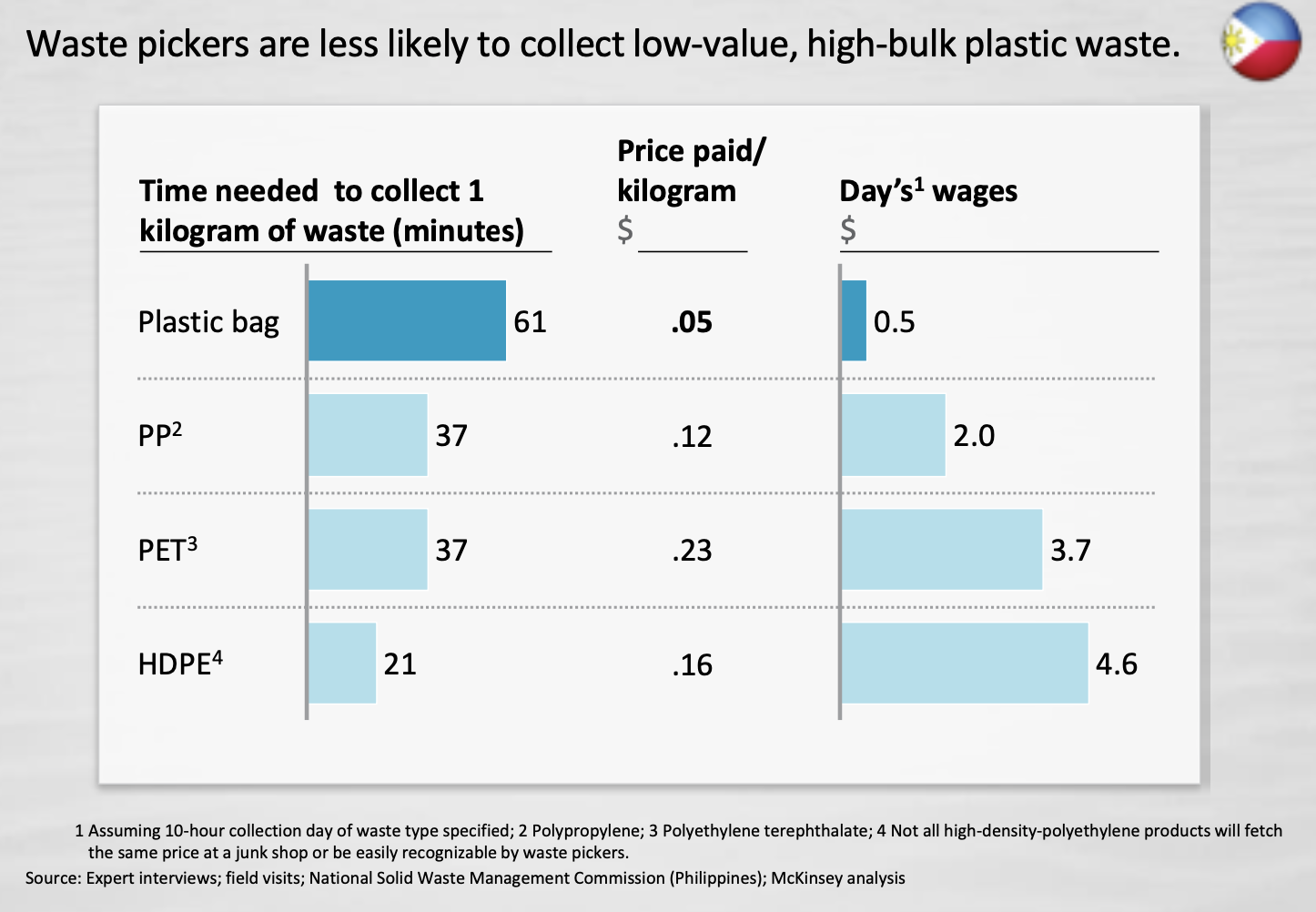

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

Reduce, reuse and recycle

There is only good in knowing these numbers however alarming they may be, because what cannot be measured, cannot be managed. With data, plastic reduction plans can be mapped out— refusing plastic, reusing what we acquire, and adapting recycling plans at home and in the community. The system has to go beyond the home. If we can only manage to retrieve those and recycle them, we can help manage the plastic crisis.

In the Philippines, studies show that while 62.6% account for the non-recyclable plastics including the single-use plastic packaging and sachets, the remaining percentage (37.4%) of plastic wastes consist of high value plastics such as PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles and HDPE (high density polyethylene) containers like shampoo and other toiletries containers, plastic jugs for juices and sauces to name a few. These are all highly recyclable and yet end up in landfills because of two possible reasons: lack of recycling capability, and the lack of awareness among communities and households on waste segregation.

In order for Filipinos to successfully reduce, reuse, and recycle, the end points of plastic waste disposal must be always secured. There are various organizations that can help. For example, Green Antz Builders has drop-off hubs for discarded sachets and other clean and dry plastic wastes. They incorporate about 100 sachets in cement mix to make eco-bricks. Papelmeroti accepts discarded bubble wrap and other plastic wastes. The Plastic Solution collects and repurposes PET bottles to create wall fillers.

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Communities can also initiate recovery projects with local government units for the segregated collection of plastic wastes to turn them into cash, or to mobilize junk shop projects. Constantino shares that as of last inquiry, the PET bottles are worth P5.00 per kilo, while P17.00 per kilo is the going rate for plastic bottle caps. The Department of Trade and Industry has also created an income forecast for communities, such as condo complexes, to start their own plastic collection and junk shops.

If the nation can recover the 37.4% of high-value plastics and recycle them, the plastic crisis in the Philippines can slowly be mitigated. If single-use plastics are refused, while others are reused and recycled, manufacturers will eventually redesign their products to adapt to the discerning, environmentally-aware public.

Mano po, Ninong

Mano po, Ninang

Narito kami ngayon

Humahalik sa inyong kamay

Salamat, Ninong

Salamat, Ninang

Sa aginaldo pong inyong ibinibigay

This timeless Christmas song by lyricist Ador Torres and composer Manuel Sr. Villar illustrates how popular godparents are during the holiday season, particularly in the aspect of gift-giving. During this time, jokes about being hunted down by a deluge of aginaldo-seeking godchildren are common, as if giving cash or gifts is the sole duty of the ninong or ninang. But is this really all there is to being a godparent?

Godparents, a brief history

According to Suzanna Roldan, who teaches Sociology and Anthropology at the Ateneo de Manila University, the ninong and ninang are part of the “compadrazgo relationships”, which came with Christian rituals such as baptism, confirmation, and marriage introduced by Spanish colonization. Our forefathers readily accepted the compadre/comare concept because even before the Spanish came, they had already been marking life events with rituals and social sanctions. “Anthropologists studying kinship systems observe that we consider who our relatives are based on biological, social and cultural ties. In categorizing who our relatives are, we trace blood lines, adoptive kin and kin through marriage or in-law relationships,” says Roldan. “There is one category of relatives that extends the notion of family. These are called fictive kin, or kinship established through rituals found in many, if not all, societies. In our case, the compadrazgo system is our way or reinforcing existing close kin or close social connections with people not necessarily our relatives.”

While godparents serve as witnesses to their godchildren becoming part of a religious community or a sanctioned marriage, the ninong or ninang also take on the role of spiritual guides. “If parents perished, godparents are expected to help in the spiritual formation of the child. We want godparents who can raise children as good Christians, or in the case of godparents to a couple, they can give spiritual advice on how to nurture good marital or parental relations. But this goes beyond spiritual formation and extends to the actual care of a child when the parents are unable to fulfill parental duties due to death, work, or moments when parents have to be apart from their children,” explains Roldan.

Photo by Denise Lazaro

Photo by Denise Lazaro

Selection of godparents

Until now, parents usually choose reliable godparents who are good role models, and have child-rearing values aligned with their own. Social proximity or close ties with godparents also plays a role. Roldan elaborates, “Parents select someone who is very close to the family or has regular interaction with them at the moment of selecting who the godparent would be. Our ninong and ninang are often siblings of our parents, playmate cousins, or our barkada from childhood whom we know we can entrust our children to in case something happens to us.”

Sometimes, economic reasons also play a part in the selection. “Some parents select well-known, high-status ninong and ninang whom one can turn to in times of need—even if they do not have a strong personal relationship with those individuals.” These include political figures, wealthy members of society, or someone who has achieved high occupational positions that indicate status.

Being a Godparent in Modern Times

Nowadays, it’s common to see godparents arrive in multiple pairs, crowding around the wed couple or the baptized child because of their sheer number. It’s a stark difference from decades ago, when a pair of godparents was enough to stand witness to religious rituals. As to why this has happened, Roldan offers this explanation: “Perhaps, it may be related to having less children these days compared to before. In the past, parents had more children, so they made sure to assign worthy godparents for all their children.”

Sometimes, the reason lies in having a big social circle. “For those with large friend groups and with one or two children, parents have to name more godparents per child so as not to exclude and hurt the feelings of their friends. Still, there are some who intentionally pick several godparents to compensate for the costs of the celebration, or expand the circle of elders they can approach for advice.”

Despite this practice, Grace, who has 10 godchildren, strives to fulfill her role. “I don’t get to talk to all of them except for my nephew who’s also my inaanak, but I do talk to their parents regularly. I know that most children see — and even expect — their godparents to give them gifts during Christmas and their birthdays. I think that’s okay especially when they’re young. That was how I saw my godparents too when I was a kid.”

Jason, who has about the same number of inaanak, shares that he only gets to interact with godchildren whose parents he’s still in contact with. “If I get to hang out with their parents, I also get to see my godchildren. I make small talk, maybe give cash. But now with social media, I can ask how they are from time to time. As a ninong, I look out for their welfare.”

Grace sees herself as a co-parent, ensuring that her godchildren grow up properly. She expects this same dedication from the godparents she’d chosen for her child. “There’s a saying, ‘It takes a village to raise a child’. It’s not easy to be a parent. As much as we want to provide for our kids’ mental, physical and emotional needs all the time, we can’t do it alone. And that’s where the ninongs and ninangs we have chosen, come in. After all, most of them are our childhood friends, high school and college buddies or our closest colleagues. They were there during our first crush, first heartbreak, and other milestones. So it only follows that as we go through this parenting journey, we go through it with them.”

Jason, 2nd from left, poses with his goddaughter Maya during her baptism.

Jason, 2nd from left, poses with his goddaughter Maya during her baptism.

The pandemic may discourage or even prohibit face-to-face interaction among godparents and godchildren, but phone calls, text message and online social platforms still make close communication possible all throughout the year. “Social support, particularly gift-giving during the holidays will continue. People shop online, send presents through various delivery modes. Ninangs and ninongs may send cash through online banking— at least for some sectors of society who are not affected by unemployment woes during the pandemic. We can expect more practical exchanges through social networks, or donations made instead of presents given during the pandemic,” Roldan ends.

To learn how you can enjoy a happy yet safe Christmas celebration during the pandemic, watch Be Safe: Pagiging Ligtas ngayong Holiday Season.

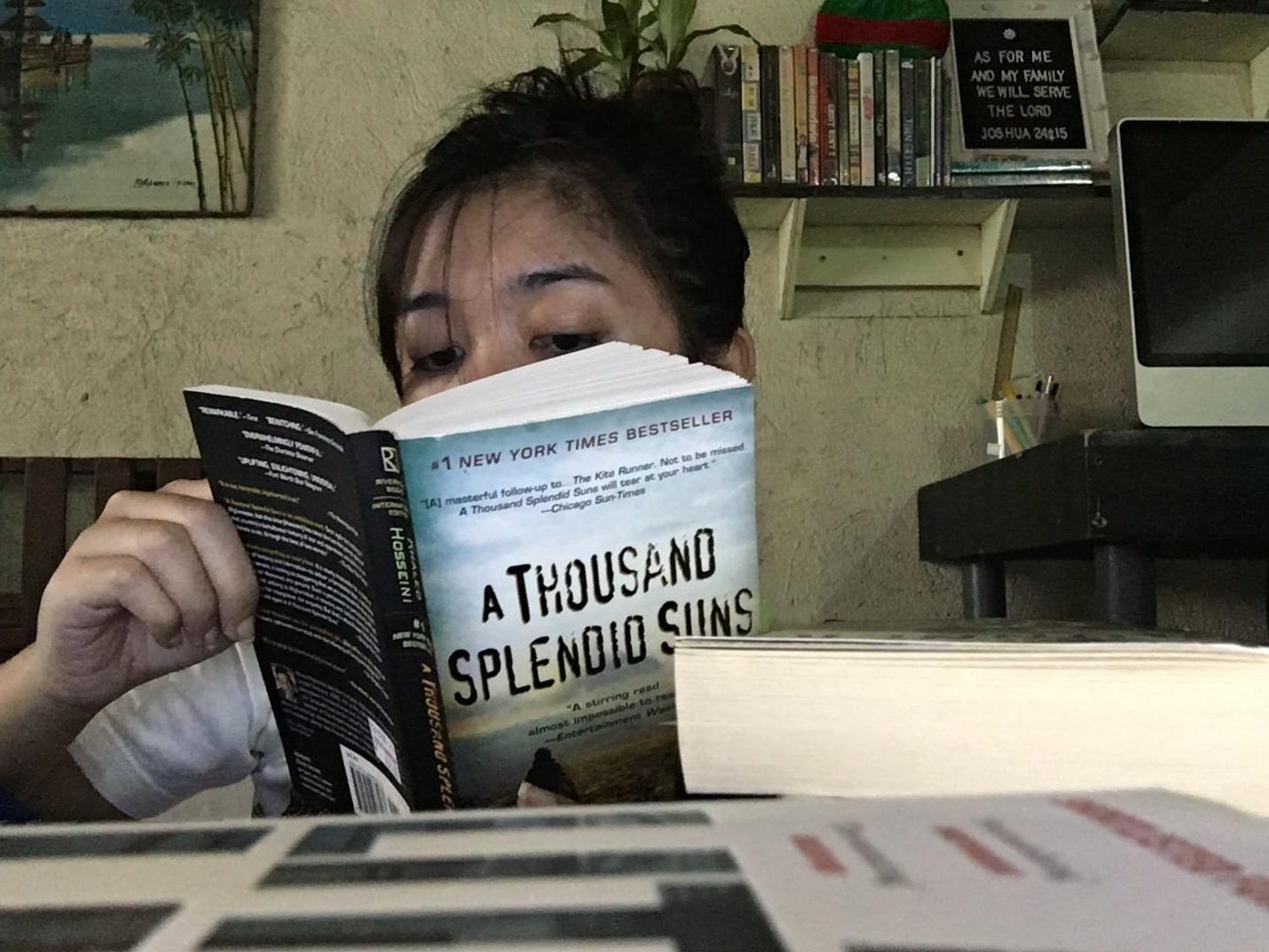

Over 300 and counting—that’s how many books Panahon TV employees have read since Executive Producer Donna May Lina launched the book report program in 2016. The rules are simple: read at least a 100-page book a month and write a review about it. Both the book and book report may be written in Tagalog or English, and the best book report gets a cash prize.

The exercise feels like a throwback to the employees’ high school days, but Lina believes that the skills learned from it remain relevant in the workplace. “As we are a content creation group, there’s a need to ensure we have a steady supply of ideas,” she shares. “One of the best ways of sharpening our comprehension and critical skills is through reading.” But Lina admits that the ultimate goal of the book report program is to develop a love for reading among her employees. “If you get to love reading and enjoy it, the possibilities are limitless. It can take you to places you have never imagined, and helps you understand the world better. Access is easier now with the e-books—or you can simply borrow books from friends and neighbors.”

Books read by Panahon TV employees are documented and filed.

Books read by Panahon TV employees are documented and filed.

Learning from Reading

Because of the requirement, non-reading employees were forced to pick up books—something they didn’t previously perceive as a leisure activity. Eventually, some of them acquired the reading habit, which not only honed work skills but also helped in coping with anxiety especially during the pandemic. It also gave them opportunities for self-improvement, particularly among employees who don’t normally write and converse in English. Though they are given the option to write their book reviews in Filipino, some still choose to write theirs in English to develop skills. Panahon TV’s head writer, who receives the book reviews, takes the time to critique each entry and encourage future submissions.

To gather their thoughts on reading, we chatted with some of the team’s regular readers.

Jun Bert Fabale

Jun Bert Fabale

Position: Website Administrator and Tricaster Operator

How have you benefited from your reading habit? Reading helps me gain new knowledge and sharpen my grammar. It’s also a good stress reliever because it keeps my focus on the book I’m reading. For a moment, I get to take a break from my personal problems.

Cris del Rosario

Cris del Rosario

Position: Motion Graphic Artist

How have you benefited from your reading habit? Aside from widening my knowledge, reading has helped improve my writing skills, which I consider one of my greatest weaknesses, along with verbally communicating with others. Now, I’m slowly gaining confidence in these areas.

Marmick Julian

Marmick Julian

Positions: Cameraman and Audioman

How have you benefited from your reading habit? I used to find myself more likely to finish a book report at the last minute, but lately, I’ve been trying to submit ahead of time. I want to continue improving my reading comprehension skills. This exercise lets me take a break from social media, which sometimes shows violent content that adds to my stress.

Charie Abarca

Charie Abarca

Position: Social Media Producer

How have you benefited from your reading habit? From the very start, I’ve always associated reading with escape. Besides the fact that reading expands my vocabulary and helps with my writing, I am thrilled that I get to do what I love and what I am required to at the same time. I have no more excuses not to read!

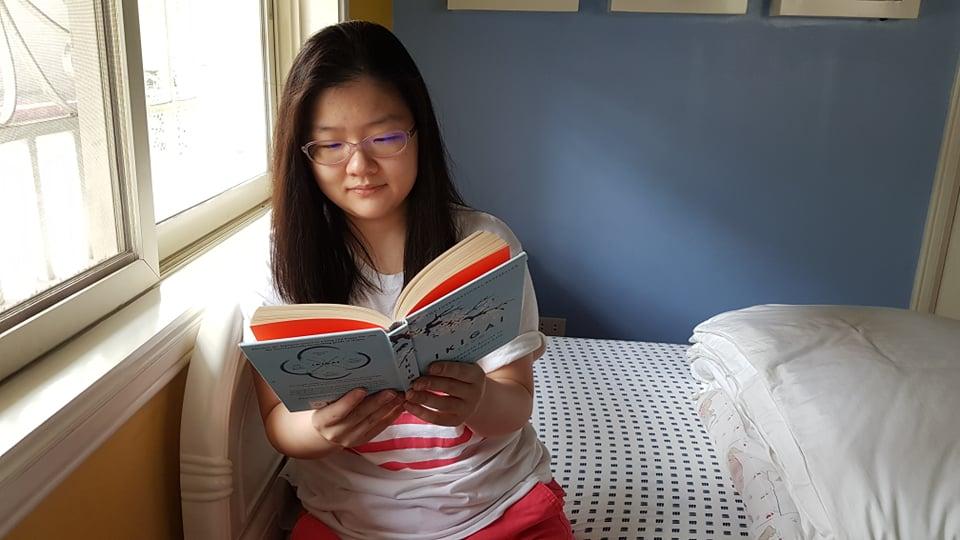

Justina Yang

Justina Yang

Position: Intern and a Broadcasting Communication student at UP Diliman

How have you benefited from your reading habit? Regular reading helps me expand my vocabulary and helps me learn new things. But more than that, reading lets me experience different worlds that I may never experience in real life. Every time I open a book, I start a new adventure with the characters. Every turn of the page is exciting because I dive deeper into the world that the book offers. This way, reading helps me forget about the current world that I live in. It’s like a temporary escape from reality, which helps me relieve stress.

Friendly Competition

The head writer used to solely determine the book report winner, but now, the previous month’s winner picks the best book review from three anonymous finalists chosen by the head writer. During the program’s weekly meeting, the previous winner presents his or her opinions about the top 3 submissions, and announces the winner. The head writer then reveals who submitted the winning entry. Lina agrees that this is a better scheme since it has “upped the ante for critical thinking” while training employees in public speaking.

Jun, who has twice succeeded in getting the top prize, talks about the exhilaration of winning. “It was a good feeling because the other book reports were also good.” Charie, who has won 3 times, shares how she writes her book reports. “There’s no magic in winning the book report of the month; I just make sure that whatever I’m submitting is close to my heart. For me, a good book scars or changes me, and successfully relays its message.” For Justina, winning was a form of validation. “The fact that my book report was chosen as a finalist, and eventually the winner meant that someone appreciated what I’ve written, and that made me feel happy.”

When asked about how they felt about choosing a winner, Jun says, “I was shocked because I didn’t know how to distinguish a book report especially if it’s written in English. But I chose the winner based on how well the submitter followed the format, and how the report effectively summarized the book.” Justina confessed that she, too, had a hard time picking a winner. “All the book reports given to me were well-written. There were even instances when I doubted my choice because the other reports were equally good.” In the end, she based her final choice on how she felt while reading the report, and the submitter’s writing style. Charie, who judged the book report finalists last month says she likes the idea of giving employees the chance to speak and choose the winner. “We get to see how someone critiques a work of art with depth. I believe that everyone have what it takes to be a winner,” she says.

Cris and Marmick speak highly of the winners. “ I admire them because they were able to clearly communicate their thoughts and feelings about the books they read. Reading their book reports is like reading the books they reviewed.” Marmick agrees. “I think good reports come from being passionate about reading. The winners effectively conveyed their opinions about the books they read.” For Lina, the reward comes when employees are “able to synthesize the put into context and application the books read. With so much ‘noise’ around, curling up with a good book is a good exercise for thinking and reflection.”

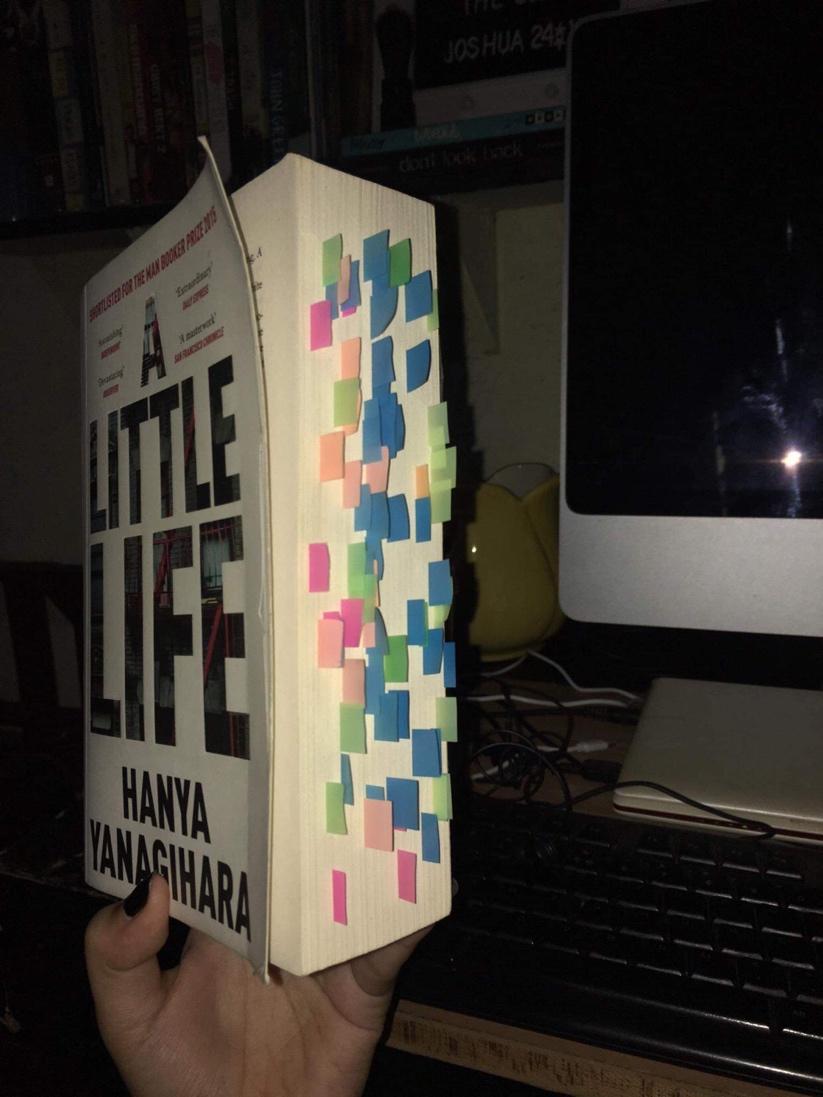

Charie’s multicolored notes in her most recent read, which was 720 pages long.

Charie’s multicolored notes in her most recent read, which was 720 pages long.

Here are the top 8 books read by the interviewees in no particular order:

- Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Live by Hector Garcia and Francesc Miralles

- The Tao of Pooh by Benjamin Hoff

- Sombi by Jonas Sunico

- All Grown up by Jami Attenberg

- A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

- Kapitan Sino by Bob Ong

- The Butterfly Lion by Michael Morpugo

- Bravo Two Zero by Andy McNab

Flooding is a perennial problem in the Philippines, which, according to PAGASA, experiences the greatest number of tropical cyclone visits than anywhere else in the world. With a yearly average of 20 tropical cyclones, the country has its share of major floods, including those from Typhoon Ulysses in November, which caused 67 deaths and agricultural damage worth 16 billion pesos.

But with climate change in the picture, the frequency and effects of disasters continue to rise. According to a report from the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, major floods across the globe has doubled in the last 20 years. Among all the climate-related disasters, storms and floods were the most common events.

Flash flood in Oriental Mindoro last Dec. 4 due to heavy rains (photo by Shen Francisco Fabon)

Flash flood in Oriental Mindoro last Dec. 4 due to heavy rains (photo by Shen Francisco Fabon)

Types of Floods

PAGASA Hydrologist Rosalie Pagulayan explains that floods can be classified according to their location and how they occur.

River flooding is caused by the swelling of rivers, also called water basins. “Just like basins, our rivers have limited carrying capacities,” she says. “If the water level exceeds these capacities, water overflows and causes floods.”

Urban flooding occurs in highly-urbanized areas. Paved roads seal off soil, which absorbs rain. Pagulayan mentions a foreign study stating that in urban places, 50% of rainfall becomes run-off water. In cases of excessive rain, drainage systems and culverts are not enough to store water, creating floods.

Meanwhile, flash floods are one of the most dangerous flood types because of how fast they rise. Possibly occurring mere minutes after rainfall, flash floods leave little or no time for residents to prepare. “These usually happen when nearby rivers are too narrow and have limited carrying capacities. Flash floods can carry harmful debris, such as rocks,” says Pagulayan.

Coastal flooding happens in coastal areas, and can be attributed to storm surges caused by tropical cyclones pushing water toward the shore. Tsunami, produced by offshore earthquakes, may also generate coastal flooding and even more devastating impacts.

Though technically, landslides are not a flood type, Pagulayan feels compelled to mention them as a significant impact of strong rainfall. “When there’s excessive rain in mountainous areas, water saturates soil and loosens it, which may lead to landslides. The steeper the slope, the faster loose soil can roll down and create devastation.”

Marikina flood after Typhoon Ulysses (photo by Jilson Tiu/Greenpeace)

Marikina flood after Typhoon Ulysses (photo by Jilson Tiu/Greenpeace)

Causes of floods

Rains are the primary cause of floods, but the flood intensity depends on numerous factors such as the affected area’s landscape and its river’s carrying capacity. “Another factor is the siltation in rivers. These sediments may lessen our rivers’ capacity to carry water, which is why the Department of Public Works and Highways carries out desilting operations.” When river protection structures such as dikes break, this leads to the sudden rush of water which creates floods. Tidal patterns also induce floods, especially in low-lying areas like Malabon and Navotas.

But a major flood contributor unrelated to meteorology is human intervention, which is a “very glaring factor” according to Pagulayan. “It’s basic science. Canopies and good vegetal cover intercept rains, protecting the soil from water saturation and erosion. Now we see that the water flowing down from the mountains are heavily silted, which means there aren’t enough trees to hold in the soil.”

River garbage is also a significant factor. “Typhoon Ondoy in 2009 showed the overwhelming amount of trash in our rivers. Rivers are a major source of our livelihood, and throwing garbage in them makes them a source of devastation.”

Typhoon Ulysses caused the Marikina River to swell and submerge vehicles in flood. (photo by Jilson Tiu/Greenpeace)

Typhoon Ulysses caused the Marikina River to swell and submerge vehicles in flood. (photo by Jilson Tiu/Greenpeace)

Flood Mitigation

To lessen the possibility of floods in the urban setting, Pagulayan suggests simple measures. “In other countries, they use cement mixed with semi-permeable asphalt so the soil underneath can absorb some of the rain. Other LGUs (local government units) put bricks on walkways instead of cementing them. I think little things like these can make a big difference in the long run.”

As for Filipinos building residences and structures near rivers, Pagulayan states, “We actually have a law that addresses this. The Water Code of the Philippines provides guidelines on how far away structures should be built from bodies of water. In urban areas, easement should be more or less 3 meters. In agricultural areas, it is 20 meters, while forest areas should have an easement of 40 meters.”

To manage coastal areas, Pagulayan emphasizes the importance of mangroves, which protect against storm surges. “Mangroves also facilitate fish development. When there are plenty of fish near the shore, our fishermen don’t have to go far.”

She shares that PAGASA carries out flood mitigation measures in two ways. “We have the structural and the non-structural. Structural involves moving the water away from the people, while non-structural is moving the people away from the water. Structural measures include the building of dams, dikes, and river walls. The main concern with the structural aspect is that it’s very expensive. To make your structures sturdy, the more you have to spend.”

Meanwhile, an example of non-structural measures is PAGASA’s early warning system, which aims to translate data into actionable information. “If we foresee a 100-millimeter rainfall, we can’t just release that data to local governments and communities. We have to give them a clear picture of the impact. Instead, we say that the projected flood is knee-deep. This way, people can better understand the situation and prepare for it.”

Aside from conducting education campaigns and public information drives, PAGASA also releases weather forecasts and tropical cyclone warnings, flood bulletins and advisories, hydrological, climatological and farm weather forecasts. “The structural and non-structural measures should complement each other. Hazard maps highlight danger and safe zones, so people will be aware where to build their homes, and where to seek refuge when they need to evacuate. With all these kinds of information, we hope to reach out to more people,” Pagulayan ends.

Watch Panahon TV Reports: Understanding Floods for more information.

Just after midnight on August 17, 1976, a magnitude 8 earthquake shook the areas around Moro Gulf in Mindanao, including Cotabato City. But the disaster did not stop there; less than 5 minutes later, a tsunami as high as 9 meters roared and swallowed 700 kilometers of coastline. When the sea ebbed to its peaceful state, around 8,000 had died from the combined effects of the earthquake and tsunami, with the latter accounting for 85% of deaths and 95% of those missing and never found. The event, now known as the 1976 Moro Gulf Earthquake, is recognized as the deadliest earthquake that ever hit the country.

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Almost two decades later on November 15, 1994, Mindoro was rocked by a magnitude 7.1 earthquake. Like what happened in Mindanao, majority of the 78 casualties of the Mindoro earthquake was due to the 8-meter high tsunami that occurred 5 minutes after the quake.

The truth is, though Filipinos are aware of devastating tsunami happening in other countries like Japan and Indonesia, they do not often associate these natural disasters in their homeland. But as past events indicate, deadly tsunami can occur locally. As Undersecretary of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for Disaster Risk Reduction-Climate Change Adaptation (DRR-CCA) and Officer-In-Charge of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) put it, “Tsunami are very fast in the Philippines and we need to prepare for them.”

Tsunami 101

In observance of World Tsunami Awareness Day last November 5, PHIVOLCS organized an online press conference to spread the word about tsunami. Mostly generated by under-the-sea earthquakes, tsunami are characterized by a series of waves with heights of more than 5 meters. According to Solidum, such earthquakes can be triggered by underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, and the more unlikely meteor impacts. These cause the seafloor to lift, causing the water it carries to rise.

There are two types of tsunami—the distant and local. Distant or far-field tsunami is generated outside the Philippines, mainly from countries bordering the Pacific Ocean like Chile, Alaska (U.S.) and Japan. With these events being monitored by The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), the Philippines has 1 to 24 hours of preparation before the tsunami’s arrival, depending on its origin.

But with local tsunami, lead time is cut down to a mere 2 to 10 minutes after the earthquake. “Preparedness is very important because rapid response is needed for locally-generated tsunami. The trenches are where the large earthquakes and tsunami can be generated, and we are only the country wherein trenches can be found on both sides. Hence, both sides of the country need to prepare for tsunami. Aside from that, the eastern side of the country faces the Pacific Ocean or the Pacific Ring of Fire where earthquakes and tsunami can also be generated,” said Solidum.

What PHIVOLCS is doing

Part of the Tsunami Risk Reduction Program of PHIVOLCS are the Tsunami Hazard Mapping and Modeling, and the Tsunami Hazard Risk Assessment, both of which aim to understand tsunami, manage their hazards and risks, and identify priority actions for response and recovery. To detect possible tsunami, PHIVOLCS set up its Monitoring and Detection Networks Development.

Aside from the 107 seismic stations that receive data for earthquakes and tsunami, there are also 29 real-time tide gauges all over the country. Through the hazards and risk-assessment software code REDAS, PHIVOLCS can evaluate potential earthquake hazards, create tsunami simulations, and predicting the number of affected people. “The total population exposed to tsunami would be close to 14 million,” said Solidum. “But they will not be affected at the same time. It would depend on where the tsunami would occur. In NCR, for example, the prone population would be around 2.4 million. And the next highest would be 1.6 million in Region VII, 1.2 million in Region VI— and in Region IXA, around 1 million.”

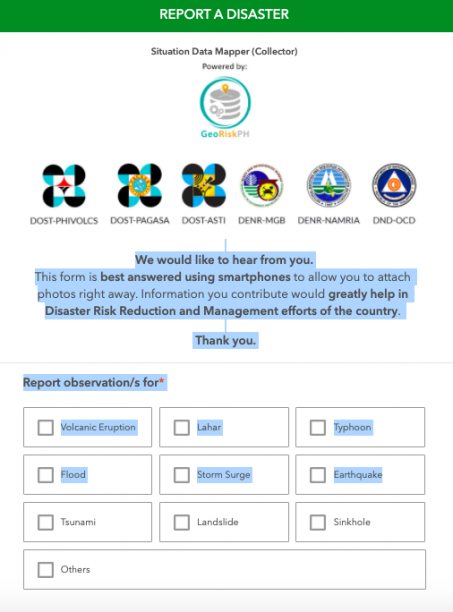

Meanwhile, HazardHunter Philippines, which is open for public use, can assess hazards depending on the user’s specific location. “HazardHunter can also give you a more detailed tsunami hazards assessment because it can provide you a map showing the different areas that will be affected by different tsunami heights. It is color coded, indicating areas prone to various tsunami heights.” Solidum appealed to the public to take advantage of the “Report a Disaster” website. Here, people can post pictures and videos of current risks and hazards in their areas, and describe disasters impacts, which can help the government’s risk and impact assessments.

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

“In the Philippines, we use a simple tsunami information or warning scheme,” explained Solidum. “We will evacuate once the tsunami information is categorized as a tsunami warning. We expect a destructive tsunami of more than 1 meter and this would need immediate evacuation of coastal areas. Boats at sea are advised to say offshore — in deep waters.”

Shake, drop and roar

Because local tsunami can be very fast, people need to know its natural signs:

Shake – refers to a strong earthquake.

Drop – refers to the sea level receding fast.

Roar – refers to the unusual sound of the returning wave, which indicates a tsunami.

After an earthquake, Solidum recommends for people near the shore to immediately move to elevated ground inland, or take refuge in tall and strong buildings. “If they have not moved at all, once they hear the tsunami and there are unusual sounds, there might not be enough time. They really need to respond immediately,” warned Solidum.

PHIVOLCS also released tsunami safety and preparedness measures on their website:

- Do not stay in low-lying coastal areas after a felt earthquake. Move to higher grounds immediately.

2. If unusual sea conditions like rapid lowering of sea level are observed, immediately move toward high grounds.

3. Never go down the beach to watch for a tsunami. When you see the wave, you are too close to escape it.

4. During the retreat of sea level, interesting sights are often revealed. Fishes may be stranded on dry land thereby attracting people to collect them. Also sandbars and coral flats may be exposed. These scenes tempt people to flock to the shoreline thereby increasing the number of people at risk.

Solidum stressed the importance of community-based preparedness, built on planning and drills to create the following output:

- development of evacuation plans based on the hazard maps

- installation of different types of signage (signage for hazards, signage for the evacuation area, signage for the directions to go to the evacuation area)

- conducting of seminars and lectures

- drills

Tsunami preparedness during COVID-19

The devastation of several typhoons this year, coupled with the country’s location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, are proof that the Philippines is prone to various hazards. Because of the

COVID-19 pandemic, Solidum admitted that PHIVOLCS had to rethink their training methods. “Before, we actually go down to various coastal communities and conduct lectures in the evening, so that people who worked in the daytime can also attend. But the pandemic has enabled more people to listen because of the social media platform and our webinars. We’ve reached more people in terms of information campaign. But we hope that local government disaster managers will do the actual preparedness at the community level.”

Solidum noted that though COVID-19 continues to cause loss of lives and the disruption of public services, mobility and economic development, tsunami can create far more devastating impacts. “We will see the physical impacts through buildings, infrastructures, property, water supply pipes, electrical supply, communication system, roads, bridges, and ports. This is in addition to the physical impact on people because of the collapsing houses or the impact of the large volume of water. We have science, technology, and innovation from DOST that can help in preparedness and disaster risk reduction. We need to use it, but we need to share this information to the communities and the public,” he ended.

Watch the full press conference from PHIVOLCS.

Watch Panahon TV’s primer on tsunami.

Within a month, from October 11 to November 12, a total of 8 tropical cyclones entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility—something that had kept weather forecasters from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) constantly on their toes. As an attached agency of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), PAGASA is mandated to “provide protection against natural calamities. and utilize scientific knowledge as an effective instrument to ensure the safety, well-being and economic security of all the people, and for the promotion of national progress.”

Though the PAGASA team comes up with the weather forecasts and tropical cyclone warnings, viewers often see this information relayed by the TV networks’ reporters. This time, Panahon TV trains the spotlight on some of the Watchers of the Atmosphere themselves—the weather specialists that tirelessly work behind the scenes to constantly monitor all weather disturbances that pose a threat to our country.

Name: Chris Perez

Positions: Senior Weather Specialist

Immediate Supervisor, Weather Forecasting and Marine Meteorology Services Sections

Master’s Degree in Climate Change at the Australian National University in Canberra

Workshops Attended: The International Workshop for Weather Presenters in Vietnam (2015), Information and Communications Technology for Meteorological Services in Korea (2006)

How did you end up as a PAGASA weather forecaster?

After passing the Electronics and Communications Engineering Board Examinations in 2000, I worked in the private sector for 2 years. I then worked at PAGASA as a weather facilities technician, calibrating weather instruments. Then I applied for the one-year Meteorologist Training Course, which I passed. I was assigned to the Weather Forecasting Section in 2005.

What are your current duties?

Currently, I am tasked to oversee the day-to-day operations of the Weather Forecasting and Marine Meteorology Services Sections, particularly the formulation and dissemination of forecast products. Occasionally, I act as the agency’s spokesperson during inclement weather conditions.

What is your most memorable typhoon?

Super Typhoon Yolanda in 2013 because it exposed the weaknesses in our country’s disaster preparedness. It was the first time PAGASA issued a forecast while a cyclone was still outside the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR). I was part of the team that attended and updated the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) prior to Yolanda’s entry to PAR.

Name: Ariel Rojas

Position: Weather Specialist

Master’s Degree in Meteorology at the University of the Philippines

Workshop Attended: Reinforcement of Meteorological Services in Japan (2019)

How did you end up as a PAGASA weather forecaster?

I was born and raised in Bicol where it always rains and tropical cyclones always visit. However, in college, I took up BS Food Technology. When I graduated in 2013, there was a brain drain of weather forecasters, so I applied for graduate school to study Meteorology under a PAGASA scholarship. When UP [University of the Philippines] shifted its academic calendar in 2014, I applied for a voluntary internship in forecasting, where I gained a lot of knowledge. I graduated in June 2017 and started working as a forecaster by November.

What are your current duties?

My main duties include analyzing weather data, maps, and models to formulate weather forecasts, and presenting the forecast product to the public through PAGASA’s online platforms and interviews with media outlets. I also conduct lectures on weather forecasting or other weather-related topics to media practitioners and students.

What is your most memorable typhoon?

I have several. The back-to-back strike of Urduja and Vinta in December 2017 because I’d been working in PAGASA for barely a month then. I cried over the number of deaths from the landslide and mudflow, especially during the passage of Vinta several days before Christmas.

Ambo this 2020 was also very memorable because it was the first typhoon during the pandemic. The forecasters and observers on duty were all holed up in the office to minimize the virus exposure. I was on duty for 9 straight days.

Rolly is also one for the books as it is the first super typhoon I’ve monitored since my employment in PAGASA. It started as a very small typhoon, the smallest I’ve seen on this side of the world. Tracking Rolly was very tricky as its forecast track kept changing due to the high pressure area which weather models weren’t able to properly project. Then it erupted into this year’s strongest cyclone and made landfall in my hometown Bato, Catanduanes, where my father was. It was very personal for me. I was trying to keep myself together while doing weather reports and updates left and right, but deep inside I was worried to death about my father’s situation. We sent him back to the province prior to the lockdown to keep him safe from COVID-19. Our town reported zero casualties and two days after the landfall, a cousin of mine shared a video of my father telling us that he’s okay.

Name: Benison Estareja

Position: Weather Specialist

Master’s Degree in Applied Meteorology and Climate with Management at the University of Reading (United Kingdom)

How did you end up as a PAGASA weather forecaster?

After graduating from the Southern Luzon State University with a degree in Electronics Engineering, I taught in the same school for two years. I was required to take my master’s but at that time, I wasn’t ready to fully commit to teaching. I heard about the Meteorologist Training Course from PAGASA, so I applied. When I got in, I quit my teaching job. The training lasted for eleven months. During that time, I realized that I’ve always been interested in forecasting. I remembered that when I was a kid, I’d see Ernie Baron on television. I told my mom that I wanted to be like him.

What are your current duties?

As one of the weather forecasters, I make PAGASA’s products such as the 5-day Weather Forecast, Asian Forecast, and the Tourist Destination Forecast. We write them and disseminate to PAGASA’s regional divisions and through social media. We also act as weather reporters on our YouTube and Facebook accounts every 5 a.m. and 5 p.m.

What is your most memorable typhoon?

Tropical Storm Mario in 2014 is memorable because it happened during my first week in PAGASA. Back then, I was living in Marikina and I couldn’t go to work because of the floods. It was ironic because the very thing I was supposed to work on was the same reason I couldn’t work. I called my supervisor, who, thankfully, understood why I couldn’t go to the office.

Estareja at work

Estareja at work

Rojas on his first day of work with other forecasters (2017)

Rojas on his first day of work with other forecasters (2017)

Challenges of Weather Forecasting

The weather forecasts Filipinos see on TV or hear over the radio may be concise and clear, but these are products of a tedious process built on data-gathering and sound decision-making. Rojas explains, “Weather presenting is only the tip of the iceberg. Forecasters analyze weather data, maps, and models to come up with the final forecast and all of these take time. Tropical cyclone events require more time and harder analyses.”

Estareja stresses that weather forecasting doesn’t only involve weather forecasters. “We get observations on different components such as temperature, rainfall, and wind from PAGASA stations scattered throughout the country. We also rely on radar observations. Satellite images from Japan and the U.S. are also very important.” To come up with the best possible forecast model, forecasters also gather data from the Japan Meteorological Agency, the Global Forecast System (GFS) from the United States’ National Weather Service, and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF). “All these are bases for a weather forecast,” explains Estareja. “We see how consistent a piece of information is across all the models. From there, we decide on our output.”

Sometimes, forecasters are required to appear on television—a challenge that, Estareja admits, can be quite daunting. “Most of us are graduates of science-related courses with no background on communication. We had to learn those skills on the job.” To support such skills, Ube Media, Inc., which produces Panahon TV, held workshops for the forecasters. “We were taught the proper way of being a TV weather presenter—

from good grooming to being mentally and physically prepared. We even learned voice modulation to give emphasis on the certain points of a report,” says Perez. Estareja shares he has gained confidence from the workshops. “I learned how to move in front of the camera, the proper use of hand gestures, and how to emphasize words and emotions.”

To help PAGASA’s weather forecasts reach the younger set, Estareja has utilized social media with his Weather Wanderer persona. Combining his passions for travel and the weather, Estareja breaks down and simplifies weather forecasts—a move that has earned his Facebook page more than 8,000 followers to date.

PAGASA’s team of weather forecasters during the country’s first typhoon (Ambo) of the year

PAGASA’s team of weather forecasters during the country’s first typhoon (Ambo) of the year

Fulfillment from Forecasting

As the most tropical cyclone-visited country in the world, our weather forecasters have their work cut out for them. “We are in the business of saving lives—in the magnitude of thousands and millions all at once during the passing of tropical cyclones,” says Rojas. “It is a very tricky profession given the chaotic nature of weather (which we try so hard to predict) and the physical toll the work inflicts. But it’s a vocation. The fulfillment comes from knowing that thousands of lives are saved.” He says he is comforted when the public understands the magnitude of harm coming their way and is able to prepare for it. “I still have a long way to go but I try my best every single time. It’s not easy but then again, saving lives has never been easy.”

Perez echoes this sentiment. “When during and after a storm, there are no reports of inclement weather-related casualties, when the areas affected are able to recover quickly, when amidst the current pandemic, we still give reliable and timely weather and climate information that can further aid our frontliners in the delivery of the medical products and services for our countrymen—these are just some of the things that give us a sense of fulfillment.”

Estareja, a former teacher, also finds fulfillment in molding the youth. “A lot of them message me, telling me they also want to be PAGASA weather forecasters. It’s heartening to know that they are our future. I encourage them to finish a science-related course and continue improving their craft. Then they can fulfill their goal of working in PAGASA.”

But weather forecasters also have their goals for PAGASA. “I want PAGASA to be the best source of weather information for the Filipinos. I want it to be at par with the other weather agencies in the region. The agency has some of the most dedicated and most competent people in civil service and they need all the support and resources they can get to help the Philippines and the Filipino people weather hydrometeorological hazards,” says Rojas.

Estareja talks about the proliferation of weather forecasts on social media. “On Facebook, you see a screenshot of a satellite image and whoever uploaded it gives his or her own forecast. Other people research on the internet, and give their own forecasts.” This, he says, diverts public attention from PAGASA’s official forecasts. “A wrong interpretation of data can be a matter of life and death. Relying on bloggers or forecaster wannabes can be dangerous. At the end of the day, we want people to look at our forecasts and treat them as if their lives depended on it.”

For Perez, such goals are reachable with PAGASA’s continuous commitment to the Filipino people. “The agency will always be monitoring weather and climate-related events for them at all times, and it will continue to provide timely and reliable weather and climate information they can use for disaster preparedness, mitigation, resiliency and the further advancement of the country’s economy.”

Agay Llanera

An hour before midnight on October 26, 1978, Super Typhoon Kading was at its peak in the country, bringing torrential rains that caused the water level at Angat Dam to swell. Because stored water, when reaching a critical high level, might cause dam structures to break, the National Power Corporation (NPC) opened all its three floodgates to 8 meters. As the rains continued to pound, adding to the dam’s water level, NPC decided to further open the floodgates to its maximum height of 14 meters by 6 a.m. the next day.

This result was a catastrophe. With the sudden dam release, several towns in Bulacan near Angat Dam was instantly flooded. But the damage in houses, farms and working animals amounting to millions of pesos was not the only tragedy; with the dam’s spillways being opened without prior warning while residents were asleep, almost 200 people died in the sudden floods.

Civil suits were filed against NPC. Complainants all attested that they had not been warned of the maximum water release. Lives could have been saved if the dam release operation was done earlier and more gradually, and if there were proper communication among the sectors involved. In 1993, the suit was won, and NPC settled by giving 5 million pesos to families of those who had died.

But the tragedy was a wake-up a call to the government, which recognized the protocol gaps in dam release. In 1983, it began the Flood Forecasting and Warning System for Dam Operation. Implementation began in 1990, while the system became fully operational in 1992. The project led to the establishment of the PAGASA Data Information Center, flood forecasting and warning systems in both PAGASA and dam offices, hydrological stations, warning posts, and repeater and monitoring stations.

MARIS Dam in Nueva Ecija releases water (photo courtesy of NIA-Magat River Integrated Irrigation System)

Giving a dam(n)

PAGASA aims to manage the flooding risk caused by dams with its daily-updated products and services:

- Basin Daily Hydrological Forecast

- Flood bulletins

- General Flood Advisories (GFA) – Regional

- Status of Monitored Dams

Rosalie Pagulayan, a hydrologist at PAGASA, emphasizes the importance of risk management in harnessing the full potential of our dams. “Major dams are multipurpose,” she says. “They generate power, irrigate farms, provide potable water and controls flooding. During the rainy season, the dam stores excess water, keeping it from inundating the rivers and communities.” Angat Dam, in particular, provides 97% of Metro Manila’s water requirements, and irrigates 31,000 hectares of farmlands in Pampanga and Bulacan.

Though dams are meant to prevent flooding, extreme weather events that bring massive rains can force dam operators to conduct water releases.

But even the frequency of tropical cyclones in our country is a double-edged sword. “Many complain about the inconvenience of the rainy season, but upon studying our climate, a former PAGASA director was able to determine that 50% of our rain comes from tropical cyclones. If we don’t have tropical cyclones, our water supply suffers. Other weather systems are also important; the northwest and southwest monsoons bring 38% of our rain, while the ICTZ [intertropical convergence zone] brings 12%.” She adds that rains are important in crop irrigation and pushing out atmospheric pollution.

Pagulayan, who has been working in PAGASA for 15 years, says that there are protocols before spillways are opened. “Even before a typhoon comes, we predict how much rainfall it will bring. We give the data to the different dam offices, which compute the expected increase in water levels. To accommodate the incoming rain, the dams conduct pre-release—but only according to the river’s capacity to prevent flooding.” She adds that aside from measuring the amount of rain in the watershed, PAGASA also measure the rain’s impact. “There’s a warning post from dam offices before they release water. There’s ample lead time, so for example, if they’re opening the gates at 4 p.m., they warn residents as early as 10 a.m. so they can prepare.”

How flooding risks can be better managed

In other parts of the world, river systems span countries, such as the Brahmaputra River, which comes from India but flows downstream to Bangladesh. The famous Danube River also comes from several European regions. Such a situation calls for strong international coordination when the source of the river swells, and flows down to various countries and territories in low-lying areas.

But Pagulayan says this is not a problem in our country. “We are blessed with big river systems. We manage our own rivers, and solely benefit from them. Our rivers traverse through various municipalities, provinces and even regions.”

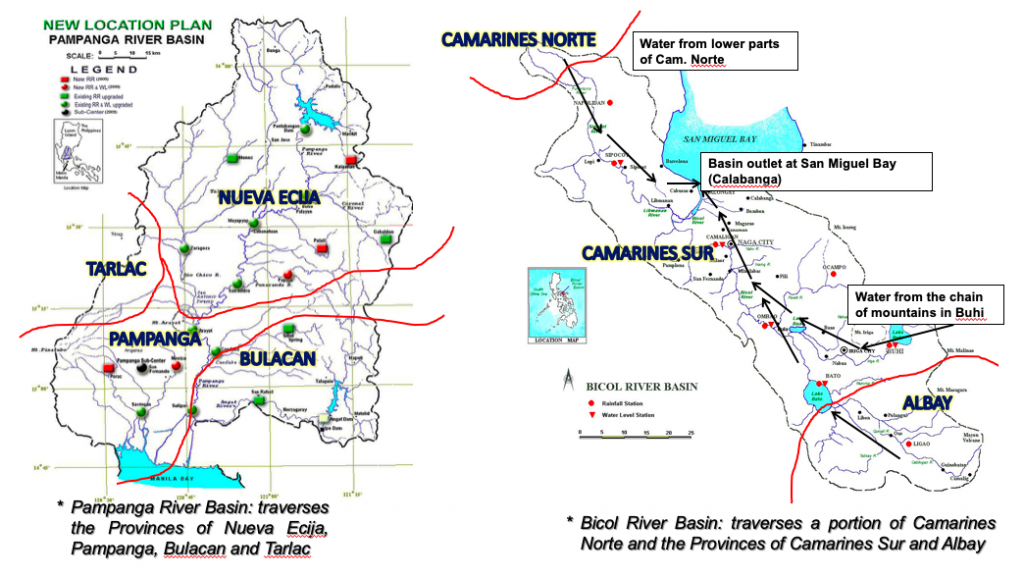

In the left graph above, Pagulayan shows how water from Nueva Ecija flows down to the Pampanga river basin, and contributes to a portion of Tarlac and Bulacan. “Our river systems encompass a lot of areas so disaster managers in these zones should be seamless in their communication and info-sharing.”

Meanwhile, as shown in the right graph above, water from the Bicol river basin comes from Albay, Camarines Norte, and mostly Camarines Sur. “But the Camarines Norte source is very important because rains are strong there, and because of its elevation, water flows down very fast,” shares Pagulayan. “All these rivers are owned by the Philippines. We don’t share them with other countries or regions. We are the only ones who can harness their potential.”

In areas that receive a lot of rain, dams and water reservoirs are built in mountainous areas, which can hold excess water. But watershed deforestation is an issue, leading to its decreased capacity for water storage. This may lead to flooding during the rainy season, and water supply shortage during the hot and dry season.

Risks also increase when people build their homes and livelihoods near waterways and flood plains. “They may find it convenient to set up livelihoods that require water, such as farms, in those areas, but once water is released, their safety is compromised,” explains Pagulayan. “Flooding also negates development efforts, and destroys agricultural products and infrastructure. But the worst risk of all is the loss of lives.”

MARIS Dam’s spillway in Nueva Ecija (photo courtesy of NIA-Magat River Integrated Irrigation System)

Moving forward

To foster good relations with dam offices and local government units (LGU), PAGASA regularly conducts information and education campaigns, public information drives, and communication drills. “For every disaster, the challenge, I think, is communication, so this is what we constantly develop. We can’t stop; it has to be continuous so we can improve,” Pagulayan shares.

By practicing and strengthening the information flow from PAGASA down to the regional and municipal levels, data accuracy is ensured, allowing LGUs to map out action plans to lessen flooding impacts. “We learn from every experience how to convey data and information. We are open to change and we adjust our activities, so we can improve both our services and community action,” ends Pagulayan.

Communities can also mitigate risks by knowing what to do before a tropical cyclone arrives and causes flooding.

Eight months into the quarantine, the pandemic is not the only life-devastating issue Filipinos are dealing with. With Super Typhoon Rolly making landfall in Bicol and CALABARZON last November 1, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) has so far reported 20 deaths and more than 2 million people affected.

A day after the disaster, the Department of Health (DOH) urged local government units (LGUs) to strictly enforce measures and prevent the spread of COVID-19 in evacuation centers. Compounding the problem are the unstable power and water supply in Bicol, and health workers unable to report for work because they, too, have been victimized by the typhoon.

Despite this downpour of risks, the most effective way to empower the public is through clear and constant communication. Awareness, which leads to preparedness and actionable information, helps save lives. With the pandemic redefining the Filipinos’ way of living since the first quarter of the year, has the government’s info campaign against COVID-19 successfully achieved these goals?

To gather insights, Panahon TV sat down with communication veterans—Tony, an executive creative director and managing partner of a Manila-based advertising agency; and April, a freelance creative creator, who formerly taught visual communication at the University of the Philippines Diliman, and also worked as a creative director in an advertising agency.

The Fight against COVID-19 as an Advertising Campaign

Tony shares that an advertising campaign begins with a client brief, which outlines its challenges, objectives and measurement of success. Before creating the campaign, a solid strategy needs to be in place. “The accounts team fleshes out the brief to make it more inspiring for the agency, and to figure out ways of attacking the problem. They profile the target market and come up with the message from the brand’s perspective. The agency’s work is to combine that message with a human story. We create the campaign, and eventually, we produce. So the crucial part is really the creative thinking before the creatives.”

April stresses the importance of seeing the brand through the consumer’s eyes. “You should know what’s already in their minds to influence their thoughts—if there’s a mindset you want to change, if you want them to listen to you for a product sell. Then you ask what you can offer that the other products or services cannot.” After analyzing the target market, a communication plan is formed, outlining the key touch points with the consumer, including the best ways to reach them.

When asked to give a general evaluation of the government’s COVID-19 info campaign, Tony feels that the basic question, What do they really want to say?, is not being addressed. “Everything seems muddled. It’s not clear whom they’re talking to or who’s doing the talking. Who’s the face of the COVID campaign? Is it the DOH secretary? The IATF [Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases]? Or is it the president?” Having different faces for the campaign may lead to information overload, leaving the public confused about what they really need to do.

When the virus entered the country, various LGUs released announcements of their first COVID-19 cases. With inappropriate visual elements, some notices ended up looking more like party invitations than serious declarations. “One of the layouts used is from Canva [an app that provides free graphic design templates],” April observes. “To me, this suggests a mismanagement of funds and the failure to tap the right professionals.”

LGU’s notice on its area’s COVID-19 cases

LGU’s notice on its area’s COVID-19 cases

On DOH’s Bida Solusyon Campaign

With financial aid from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), DOH launched its “BIDA Solusyon sa COVID-19” campaign last July. Supported by various sectors including top corporations and industries, the campaign promotes these four key preventive steps:

Bawal walang mask.

I-sanitize ang kamay at iwas-hawak sa mga bagay.

Dumistansya ng isang metro.

Alamin ang totoong impormasyon.

A quick look at the campaign’s Facebook page reveals a comics theme, with messages incorporated into brightly-colored panels that feature real-life characters wearing superhero costumes. April and Tony both agree that the messaging is outdated.

“I’d imagine the person who commissioned this to be an old practitioner of advertising—that’s his idea of what a witty campaign is,” comments April. “It relies on mnemonics and catchy phrases, without customizing communication for each message.” She cites an infographic for senior citizens that looked forced since the campaigner insisted on incorporating the comics theme and BIDA tagline. “When that happens, you sacrifice function for form, and you end up not communicating at all. You need to mine your audience’s insight to communicate with them. And because the campaign messages are all the same, people might not bother reading them.”

(grabbed from the campaign’s Facebook page)

(grabbed from the campaign’s Facebook page)

Though Tony recognizes the campaign’s thrust to empower the public, he feels that its messaging could be more urgent. “It’s an old DOH style from ‘Yosi Kadiri’ days. And I think for COVID, we should stop all of these witty, pa-funny, pa-cute campaigns. You can’t express the gravity of the situation with a campaign like ‘BIDA’.” Tony also points out that the government campaign needs stand out in a sea of public service messages from brands and corporations. “Information should be readily available to the public. It has to be ubiquitous. The problem is that different LGUS make their own campaigns, so the messaging and looks vary. The campaign should be centralized to gain maximum impact.”

Ways to Improve the Campaign

Tony considers fake news and its many forms, such as misinformation and disinformation, as the campaign’s biggest enemy. “Until now, my barber still believes that COVID-19 is a make-believe issue because no one in his barangay has contracted it. How can this be possible eight months into the pandemic?” For April, credible sources of information should be top priority. “If I were to make a brief, I’d make a quick survey to find out what the public needs to know. Then I’d employ scientists to get the hard facts on the virus.”

Carry out the campaign in phases.