Donna Lina with Agay Llanera

With the whole world racing to beat the pandemic, COVID-19 vaccinations are at the top of the global news pile. According to Bloomberg, the United States tops the list of having the most vaccinations so far at the rate of over 2 million doses per day.

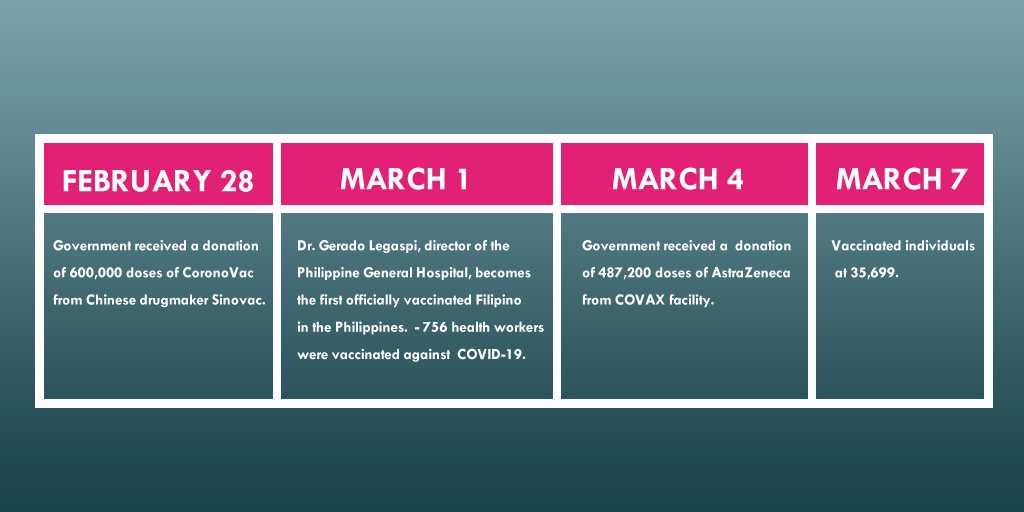

Since the start of the Philippines’ vaccination drive last March 1, the latest tally of total vaccinations is now over 114,000. Besides the delayed arrival of vaccines, another hurdle the country’s mass vaccination faces is the Filipinos’ reduced confidence in vaccines. According to a recent survey, 46% of Filipinos are unwilling to get inoculated against COVID-19 even if the vaccine was proven safe and effective.

A Brief History of Vaccines

English Physician Edward Jenner is widely recognized to have made the first vaccination in 1796. After inoculating a child with smallpox virus, the vaccinee developed an immunity to the disease. Mass immunization following the development of the smallpox vaccine led to the disease’s global extermination in 1979.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) acknowledges the crucial role of childhood vaccines in preventing the following diseases:

- polio

- measles

- diphtheria

- pertussis (whooping cough)

- rubella (German measles)

- mumps

- tetanus

- rotavirus

- Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib)

For communicable diseases, vaccines act as extra protection for the body and the entire community. To get this kind of protection, a community must achieve herd immunity.

What is Herd Immunity?

Herd immunity or population immunity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the “indirect protection from an infectious disease that happens when a population is immune either through vaccination or immunity developed through previous infection.” WHO makes it clear that it supports herd immunity against COVID-19 through vaccination.

This is achieved through mass vaccination, enabling majority of the population to be immune to the disease. Scientists are still researching how much of the population needs to be inoculated for herd immunity against COVID-19 to take place. In the Philippines, the government announced its plans to vaccinate 100% of its adult population or about 70 million Filipinos.

COVID-19 Vaccination Plan in PH

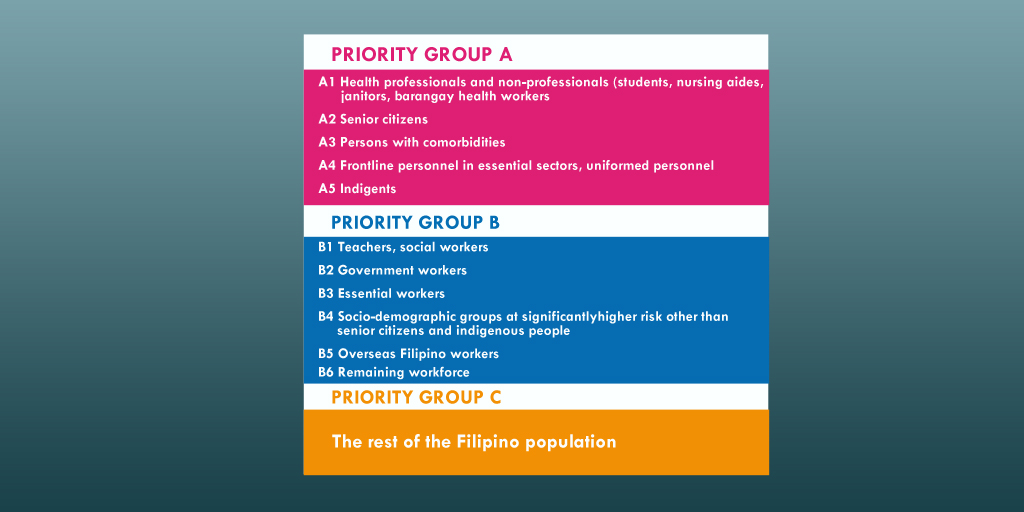

Last February, the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) finalized the priority list for the COVID-19 vaccination drive.

Source: Philippine News Agency (PNA)

Source: Philippine News Agency (PNA)

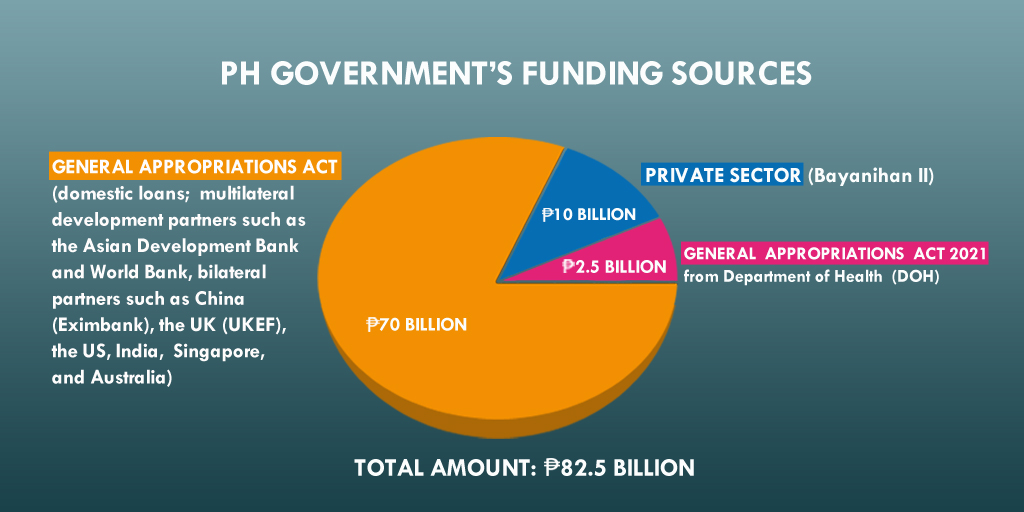

According to the Philippine National Deployment and Vaccination Plan for COVID-19 Vaccines, the government has accumulated ₱82.5 billion to cover costs of procuring vaccines, logistics, distribution and monitoring.

Source: DOH

Source: DOH

With vaccination costs pegged at ₱1,300 per individual according to Department of Finance (DOF) Secretary Carlos Dominguez III, around 57 million Filipinos will benefit from the nearly ₱75-billion funds allocated by the government for vaccine acquisition. The remaining individuals are to be covered by the local government units (LGUs) and the private sector. Under the Bayanihan to Recover as One Act, the national government, local government units (LGUs) and about 300 Philippine companies signed an agreement with British pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca to procure 17 million vaccine doses. In this article, Presidential Adviser for Entrepreneurship Joey Concepcion said that half of the vaccine doses will be given to the national government, while the remaining half are for the companies’ workforce.

Nationwide Vaccination Drive

Sources: DOH, WHO, PNA

Sources: DOH, WHO, PNA

Over 480,000 doses of AstraZeneca vaccine arrive in the Philippines from the COVAX facility. (Photo from National Task Force Against COVID-19)

Over 480,000 doses of AstraZeneca vaccine arrive in the Philippines from the COVAX facility. (Photo from National Task Force Against COVID-19)

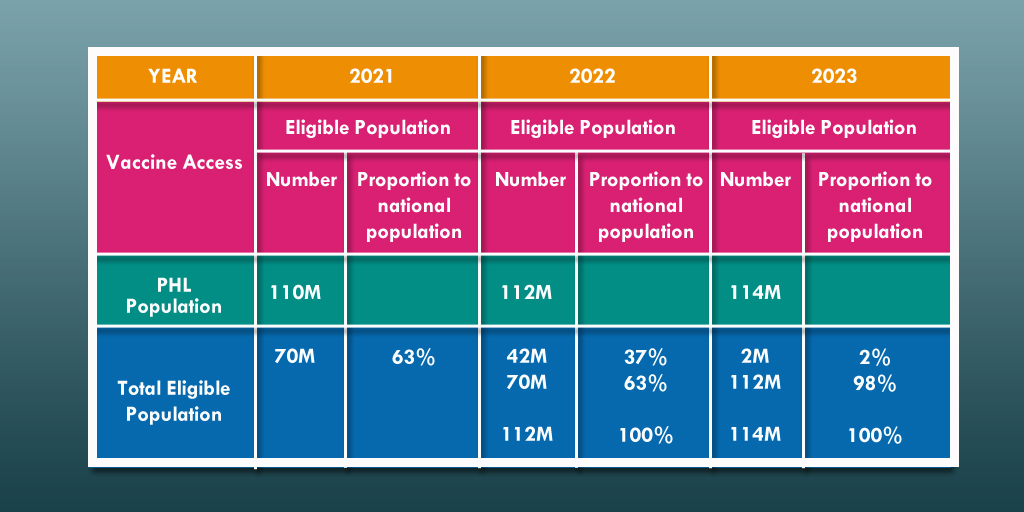

With population projections from the Philippine Statistics Authority, the government developed a three-year vaccination plan from 2021 to 2023. The roadmap assumes that by 2022, those 16 years old and below may be allowed to take the vaccine, and that by 2023, newborns can be inoculated against COVID-19. Those who’d taken the shots in 2021 will be given booster shots in the succeeding years.

Source: DOH

Source: DOH

Achieving Herd Immunity

Though WHO emphasizes that “the proportion of the population that must be vaccinated against COVID-19 to begin inducing herd immunity is not known,” the Philippine government’s goal of vaccinating 70 million Filipinos this 2021 aims to achieve herd immunity. Because each vaccination requires two doses, 140 million vaccine doses need to be rolled out in a year.

Based on such figures, the government needs to ramp up its vaccination drive to achieve herd immunity, and enable the country to recover both from the health and economic crises.

The country’s battle against the pandemic is still unfolding but one thing remains clear: until the crucial number of 70 million have not been vaccinated, Filipinos need to be on their toes as cases continue to surge.

Time is of the essence, but with majority having no means for vaccination yet, basic health and safety measures are still the strongest defense against this disease which continues to add to the global death toll of over 2 million.

Plastic-wrapped nation. Illustrated by sticker artist Zahnina Jayne Rosal ©2020

Nearly everything we use in our daily lives is made of plastic. We start the day by using a plastic toothbrush. To save money, we pack meals in a plastic container. On the way to the office, we pick up coffee in a disposable cup, which sometimes comes with disposable plastic straw. At the office, we attend a meeting that serves water, juice, or soda in PET bottles.

These modern conveniences seem harmless but in abundance, compounded by habitual improper waste disposal, is how the world has found itself nearly suffocated in plastic.

Single-use plastic is everywhere

According to a United Nations environmental report, “Our planet is drowning in plastic pollution. Around the world, one million plastic drinking bottles are purchased every minute, while up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide every year.” Half of these plastics are manufactured as single-use products, eventually discarded to contribute to the 300 million tonnes of plastic waste and debris the world produces annually.

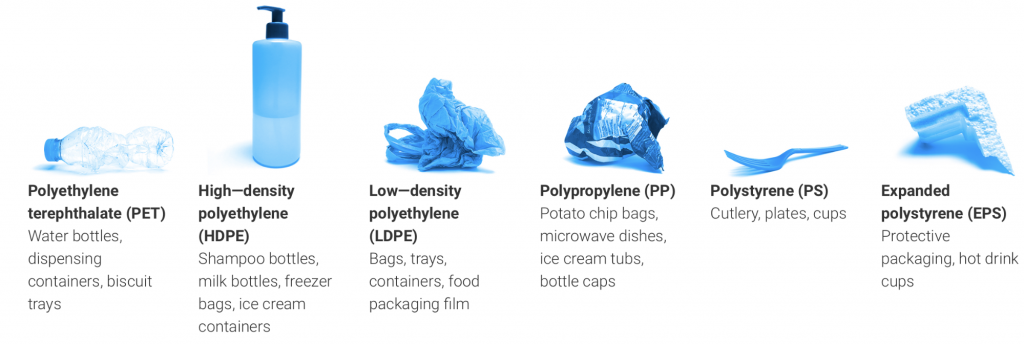

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

Different types of plastics (grabbed from UN Environment Report)

These plastic pollutants degrade into smaller fragments—from undetectable microplastic (>5mm) about the size of sesame seeds, to macroplastic (<5mm) large enough to be easily recognized in its original form. These find their way into catchments before being discharged to rivers, seas, beaches, and recently, even in remote, pristine locations like Lake Geneva in Switzerland and Lake Guarda in Italy.

The world is so littered with plastic that a recent study has indicated the presence of small pieces of plastic waste even in the remote mountain ranges of the French Pyrenees. Samples found from the mountains include microplastics likely from single-use plastic packaging from take-out food and PET bottles transported through the air.

The throw-away culture and soft plastics

In the Philippines, soft plastics are the most prevalent plastic litter found in our waters, according to Amy Slack, an environmental consultant who regularly volunteers for Marine Conservation Philippines to work with international movement Break Free From Plastic in Negros Oriental initiative. In her analysis of plastic waste collected during their group’s beach cleans in December 2019, she blogged: “Consistently, the vast majority of the debris we found strewn across the beaches across the Philippines was plastic; a significant amount of that was soft plastics which can’t be recycled – plastic bags, sweet and crisp packets, and single-use soap and detergent sachets. There were some variations though: at one beach, we kept picking up a staggering amount of styrofoam.”

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Sachets are non-recyclable multilayered, single-used plastic. © Amy Slack

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Recycling facility in Quezon City, taken during a field visit last February 2020. © Czarina Constantino / WWF-Philippines

Though their organization was able to fish out trash and segregate, another road block cropped up. According to Slack, “It became increasingly apparent that part of the problem was the variability of waste management across the municipality of Zamboanguita, in the Negros Oriental province.” Aside from the lack of resources or end-points, many locals have no recycling knowledge at all. This seems to be the case not only in the municipality of Zamboangita, Negros Oriental, but also around the country.

Meanwhile, Czarina Constantino of World Wide Fund for Nature Philippines (WWF), also the national lead for “No Plastics in Nature” Initiative acknowledges this. “Meron ‘pag Luzon, pero ‘pag mga Visayas or Mindanao, Hirap sila. Kasi archipelagic pa rin tayo. Sobrang hirap rin para kulektahin ang mga basura. Sobrang gastos. (There are in Luzon, but they’re scarce in Visayas and Mindanao because our country is archipelagic. It is very challenging to collect garbage. It’s very expensive.)

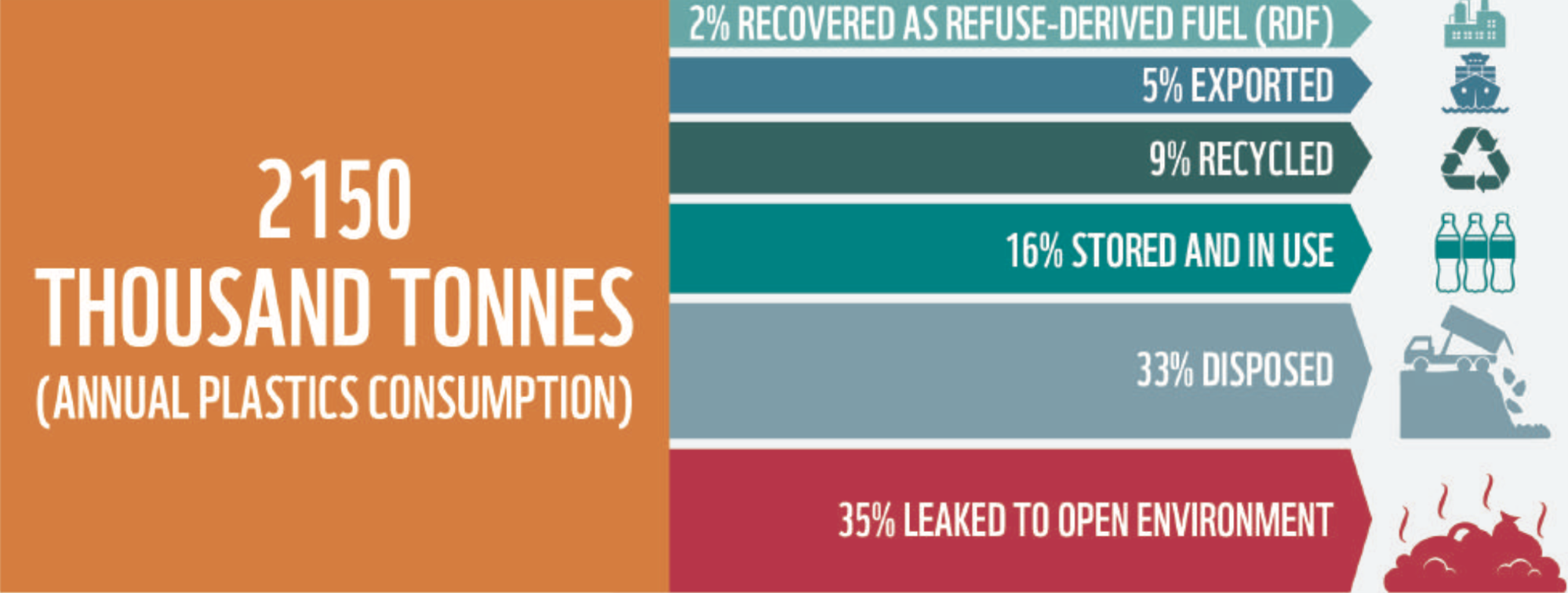

The number of recycling facilities in the country is too limited to accommodate all the plastic waste the country generates, which is about 20 kilograms per person annually, or 2,150,000 tons of plastic waste in 2019, according to the 2020 WWF findings from its recently conducted material flow analysis of plastic packaging waste.

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Flow of Plastic Materials in the Philippines in 2019 © WWF Philippines

Sachets, Extended Producers Responsibility and eco-design

Sachets are made of several layers of different types of plastic, which require separation prior to recycling. Some of these layers have very poor recyclability, and with all the mechanical steps required to separate them, it is neither economical nor profitable to recycle sachets. It is decidedly a single-use product, and a good number of case studies suggests it to be the likely culprit to our environment’s plastic woes.

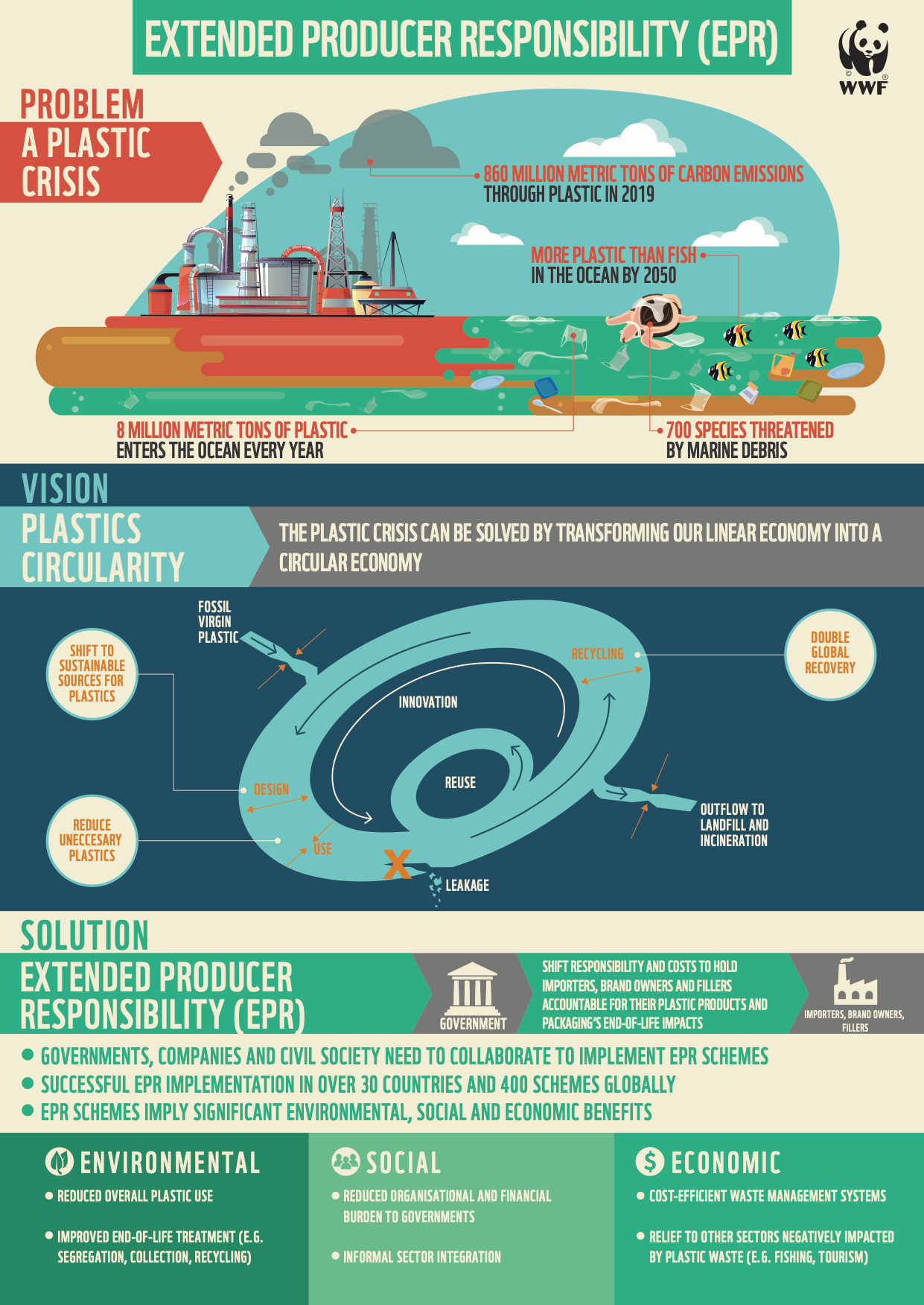

According to the United Nations, the Philippines is one of five countries from which plastic pollution originates before flowing to the rest of the world. To help address this, WWF along with Congress, are working on a legislation that shall compel producers, manufacturers and businesses to be accountable for the waste they put into the market. A scheme, here and abroad, called Extended Producers Responsibilty (EPR), shall bill them ahead for their plastic waste contribution to society. This is expected to encourage stakeholders to redesign their products with recyclability or reusability in mind to avoid exorbitant EPR fees. One of the first effects expected out of EPR is the innovation of eco-friendly plastic products. Other than RA 9003, otherwise known as the Philippine Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, this is by far one of the most aggressive steps taken towards arresting the catastrophic effects of non-recyclable plastics in our environment.

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

The plastic crisis and the Expanded Producer Responsibility promotes accountability and collaborative efforts solution. © WWF Philippines

Paper or plastic?

It is not enough to opt for paper bags while shopping. This practice potentially harms virgin forests, while reusable bags require 131 uses to qualify them as sustainable. Waste management remains an ideal option—which, unfortunately, local governments find difficult to finance. Constantino relates, “Most recycling facilities WWF has worked with are privately owned. It is also a fact that most machines that local governments own are for composting, and not recycling.”

Though the lack of recycling facilities and accessible recycling programs add to the ongoing plastic crisis, there is simply an overwhelming amount of plastic wastes, which spill out to nature and contribute to flooding issues. In this light, Constantino stresses the importance of household waste management system. “Start with ourselves. Apart from changing yourself, you also have to change the system. Practice segregation. Apart from changing your lifestyle, you have to change the system so you can influence. People can influence systemic changes in their areas.”

Plastic use in the time of pandemic

A recent study conducted in July 2020 by Pew Trusts indicates that at present, 11 million metric tons of plastics enter the oceans annually, which can possibly triple by 2040. Still, Constantino acknowledges there are necessary plastics. “We do not say that let us eliminate all plastics. For WWF, there are necessary plastics. We usually relate them to food safety and health security. If it’s something that would help decrease the food wastes, we’re okay with that.”

However, this projection has not taken into account the pandemic effect on the usage of plastics brought about by food consumption and health security. In the Philippines, our waste management solution is mostly through landfills shared by cities. Presently, the WWF has not received confirmation on whether the lifespan of these landfills will be greatly affected by the increase in plastic consumption these last few months.

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

Microwavable plastic containers collected in one month by a household of 4 in May 2020. © River Rosal

WWF expects the numbers to rise as a consequence. “While we were conversing with Manila City, ang next nilang problem, mapupuno na raw yung landfill by 2026,” Constantino shares. “That’s pre-COVID, pero ngayon hindi ko alam kung that is still the projection. Recently, there’s really a significant increase of plastic use—lalo na yung mga tao, stay at home, padeliver lahat. Some businesses, dati pwede ka magdala ng resuables, pero ngayon, kinansel muna nila due to health reason daw. Kasi parang nag-shift din yung mga businesses, na dating nag-re-reusables, or dating nag-e-entertain ng reusability, ngayon, parang stop muna natin.’” (While we were conversing with the Manila City government, they shared that their next problem is that the landfill could be filled to capacity by 2026. That’s pre-COVID, but now, I don’t know if that is still the projection. Recently, there has been a significant increase of plastic use. Because people are at home, everything gets delivered. Some businesses used to allow reusables, but these days, that option is cancelled, supposedly due to health reasons. There appears to be a shift among businesses who used to accommodate reusables, or those who used to entertain reusability. But now they’re saying, “Let’s stop for a while.”)

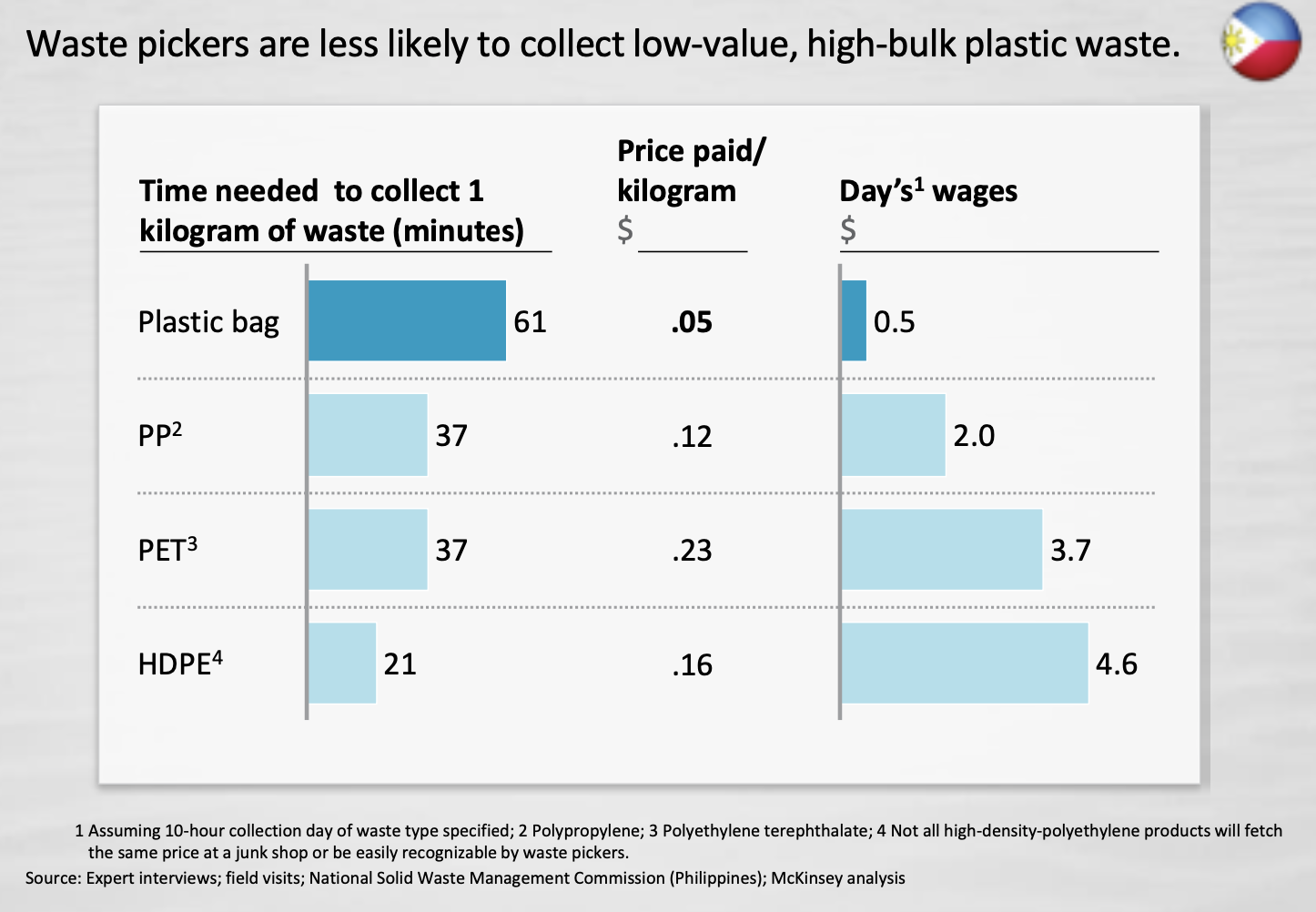

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

High-value plastic such as PET and HDPE are not prioritized by waste pickers in the Philippines. © McKinsey Center for Business and Environment

Reduce, reuse and recycle

There is only good in knowing these numbers however alarming they may be, because what cannot be measured, cannot be managed. With data, plastic reduction plans can be mapped out— refusing plastic, reusing what we acquire, and adapting recycling plans at home and in the community. The system has to go beyond the home. If we can only manage to retrieve those and recycle them, we can help manage the plastic crisis.

In the Philippines, studies show that while 62.6% account for the non-recyclable plastics including the single-use plastic packaging and sachets, the remaining percentage (37.4%) of plastic wastes consist of high value plastics such as PET (polyethylene terephthalate) bottles and HDPE (high density polyethylene) containers like shampoo and other toiletries containers, plastic jugs for juices and sauces to name a few. These are all highly recyclable and yet end up in landfills because of two possible reasons: lack of recycling capability, and the lack of awareness among communities and households on waste segregation.

In order for Filipinos to successfully reduce, reuse, and recycle, the end points of plastic waste disposal must be always secured. There are various organizations that can help. For example, Green Antz Builders has drop-off hubs for discarded sachets and other clean and dry plastic wastes. They incorporate about 100 sachets in cement mix to make eco-bricks. Papelmeroti accepts discarded bubble wrap and other plastic wastes. The Plastic Solution collects and repurposes PET bottles to create wall fillers.

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Fully packed PET bottles turned into bricks for wall partitions ( The Plastic Solution. ©2020.)

Communities can also initiate recovery projects with local government units for the segregated collection of plastic wastes to turn them into cash, or to mobilize junk shop projects. Constantino shares that as of last inquiry, the PET bottles are worth P5.00 per kilo, while P17.00 per kilo is the going rate for plastic bottle caps. The Department of Trade and Industry has also created an income forecast for communities, such as condo complexes, to start their own plastic collection and junk shops.

If the nation can recover the 37.4% of high-value plastics and recycle them, the plastic crisis in the Philippines can slowly be mitigated. If single-use plastics are refused, while others are reused and recycled, manufacturers will eventually redesign their products to adapt to the discerning, environmentally-aware public.

Most Filipinos would not rather think about disasters now that Christmas is around the corner; but the fact that the world is in the middle of a pandemic shows that crises can strike at any given time.

Given the country’s location within the Pacific Ring of Fire, and that the Philippines experiences the most number of typhoons than anywhere else in the world, Filipinos should make disaster preparedness a daily habit and part of their culture.

To help achieve this, Panahon TV, which has long advocated disaster preparedness from its birth almost a decade ago, has a timely and useful gift for Filipinos this holiday season—the gift of disaster preparedness. A free webinar moderated by Panahon TV Reporter Patrick Obsuna will feature distinguished speakers and veterans in the field of disaster preparedness. Martin Aguda, author of Ready 101 and national representative to the International Association of Emergency Managers will talk about risk awareness, emergency planning, acquiring survival supplies, and the skills and drills needed to survive disasters. Meanwhile, Sandy Montano, an earthquake survivor and the CEO of Community Health Education Emergency Rescue Services (CHEERS) will shed light on government response during disasters, and the important role of women in preparedness.

Disaster Preparedness during the Pandemic will air on December 22 at 2 pm. Though the webinar is free, monetary donations are welcome and will be given to the Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation for victims of Super Typhoon Rolly and Typhoon Ulysses.

To join the webinar, register here: https://bit.ly/2LBm5X3

Just after midnight on August 17, 1976, a magnitude 8 earthquake shook the areas around Moro Gulf in Mindanao, including Cotabato City. But the disaster did not stop there; less than 5 minutes later, a tsunami as high as 9 meters roared and swallowed 700 kilometers of coastline. When the sea ebbed to its peaceful state, around 8,000 had died from the combined effects of the earthquake and tsunami, with the latter accounting for 85% of deaths and 95% of those missing and never found. The event, now known as the 1976 Moro Gulf Earthquake, is recognized as the deadliest earthquake that ever hit the country.

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Devastation of the 1976 tsunami at Barangay Tibpuan in Lebak, Mindanao (Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

Almost two decades later on November 15, 1994, Mindoro was rocked by a magnitude 7.1 earthquake. Like what happened in Mindanao, majority of the 78 casualties of the Mindoro earthquake was due to the 8-meter high tsunami that occurred 5 minutes after the quake.

The truth is, though Filipinos are aware of devastating tsunami happening in other countries like Japan and Indonesia, they do not often associate these natural disasters in their homeland. But as past events indicate, deadly tsunami can occur locally. As Undersecretary of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) for Disaster Risk Reduction-Climate Change Adaptation (DRR-CCA) and Officer-In-Charge of the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) put it, “Tsunami are very fast in the Philippines and we need to prepare for them.”

Tsunami 101

In observance of World Tsunami Awareness Day last November 5, PHIVOLCS organized an online press conference to spread the word about tsunami. Mostly generated by under-the-sea earthquakes, tsunami are characterized by a series of waves with heights of more than 5 meters. According to Solidum, such earthquakes can be triggered by underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, and the more unlikely meteor impacts. These cause the seafloor to lift, causing the water it carries to rise.

There are two types of tsunami—the distant and local. Distant or far-field tsunami is generated outside the Philippines, mainly from countries bordering the Pacific Ocean like Chile, Alaska (U.S.) and Japan. With these events being monitored by The Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC), the Philippines has 1 to 24 hours of preparation before the tsunami’s arrival, depending on its origin.

But with local tsunami, lead time is cut down to a mere 2 to 10 minutes after the earthquake. “Preparedness is very important because rapid response is needed for locally-generated tsunami. The trenches are where the large earthquakes and tsunami can be generated, and we are only the country wherein trenches can be found on both sides. Hence, both sides of the country need to prepare for tsunami. Aside from that, the eastern side of the country faces the Pacific Ocean or the Pacific Ring of Fire where earthquakes and tsunami can also be generated,” said Solidum.

What PHIVOLCS is doing

Part of the Tsunami Risk Reduction Program of PHIVOLCS are the Tsunami Hazard Mapping and Modeling, and the Tsunami Hazard Risk Assessment, both of which aim to understand tsunami, manage their hazards and risks, and identify priority actions for response and recovery. To detect possible tsunami, PHIVOLCS set up its Monitoring and Detection Networks Development.

Aside from the 107 seismic stations that receive data for earthquakes and tsunami, there are also 29 real-time tide gauges all over the country. Through the hazards and risk-assessment software code REDAS, PHIVOLCS can evaluate potential earthquake hazards, create tsunami simulations, and predicting the number of affected people. “The total population exposed to tsunami would be close to 14 million,” said Solidum. “But they will not be affected at the same time. It would depend on where the tsunami would occur. In NCR, for example, the prone population would be around 2.4 million. And the next highest would be 1.6 million in Region VII, 1.2 million in Region VI— and in Region IXA, around 1 million.”

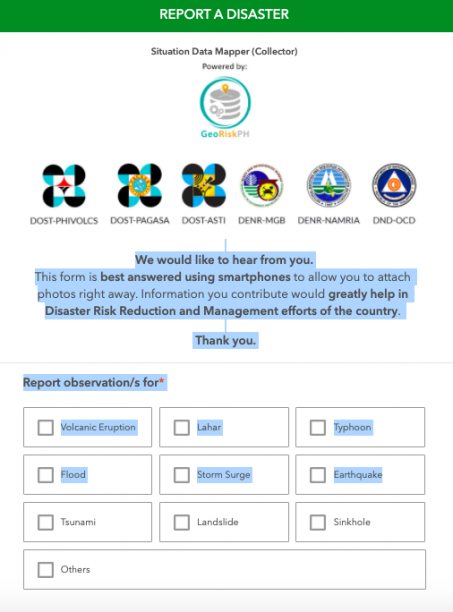

Meanwhile, HazardHunter Philippines, which is open for public use, can assess hazards depending on the user’s specific location. “HazardHunter can also give you a more detailed tsunami hazards assessment because it can provide you a map showing the different areas that will be affected by different tsunami heights. It is color coded, indicating areas prone to various tsunami heights.” Solidum appealed to the public to take advantage of the “Report a Disaster” website. Here, people can post pictures and videos of current risks and hazards in their areas, and describe disasters impacts, which can help the government’s risk and impact assessments.

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

Screencap of “Report a Disaster” website

“In the Philippines, we use a simple tsunami information or warning scheme,” explained Solidum. “We will evacuate once the tsunami information is categorized as a tsunami warning. We expect a destructive tsunami of more than 1 meter and this would need immediate evacuation of coastal areas. Boats at sea are advised to say offshore — in deep waters.”

Shake, drop and roar

Because local tsunami can be very fast, people need to know its natural signs:

Shake – refers to a strong earthquake.

Drop – refers to the sea level receding fast.

Roar – refers to the unusual sound of the returning wave, which indicates a tsunami.

After an earthquake, Solidum recommends for people near the shore to immediately move to elevated ground inland, or take refuge in tall and strong buildings. “If they have not moved at all, once they hear the tsunami and there are unusual sounds, there might not be enough time. They really need to respond immediately,” warned Solidum.

PHIVOLCS also released tsunami safety and preparedness measures on their website:

- Do not stay in low-lying coastal areas after a felt earthquake. Move to higher grounds immediately.

2. If unusual sea conditions like rapid lowering of sea level are observed, immediately move toward high grounds.

3. Never go down the beach to watch for a tsunami. When you see the wave, you are too close to escape it.

4. During the retreat of sea level, interesting sights are often revealed. Fishes may be stranded on dry land thereby attracting people to collect them. Also sandbars and coral flats may be exposed. These scenes tempt people to flock to the shoreline thereby increasing the number of people at risk.

Solidum stressed the importance of community-based preparedness, built on planning and drills to create the following output:

- development of evacuation plans based on the hazard maps

- installation of different types of signage (signage for hazards, signage for the evacuation area, signage for the directions to go to the evacuation area)

- conducting of seminars and lectures

- drills

Tsunami preparedness during COVID-19

The devastation of several typhoons this year, coupled with the country’s location in the Pacific Ring of Fire, are proof that the Philippines is prone to various hazards. Because of the

COVID-19 pandemic, Solidum admitted that PHIVOLCS had to rethink their training methods. “Before, we actually go down to various coastal communities and conduct lectures in the evening, so that people who worked in the daytime can also attend. But the pandemic has enabled more people to listen because of the social media platform and our webinars. We’ve reached more people in terms of information campaign. But we hope that local government disaster managers will do the actual preparedness at the community level.”

Solidum noted that though COVID-19 continues to cause loss of lives and the disruption of public services, mobility and economic development, tsunami can create far more devastating impacts. “We will see the physical impacts through buildings, infrastructures, property, water supply pipes, electrical supply, communication system, roads, bridges, and ports. This is in addition to the physical impact on people because of the collapsing houses or the impact of the large volume of water. We have science, technology, and innovation from DOST that can help in preparedness and disaster risk reduction. We need to use it, but we need to share this information to the communities and the public,” he ended.

Watch the full press conference from PHIVOLCS.

Watch Panahon TV’s primer on tsunami.

This year’s Todos los Santos will be celebrated differently in light of the pandemic. From October 29 to November 5, cemeteries, columbaries and memorial parks are closed as a safety measure against COVID-19. But aside from visiting their dead outside these dates, Filipinos can still continue a semblance of tradition by lighting virtual candles for their loved ones through a website initiated by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP).

A precursor to All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days is Halloween which, will now, be ideally spent at home. In Metro Manila, Western influences are strong with people holding costume parties, and trick-or-treating for kids in neighborhoods, malls, hotels and even in their parents’ offices.

A Brief History of Halloween

But what really is Halloween and how has it evolved into the colorful, festive celebration we know of today?

This tradition is rooted in the culture of Celts, who mostly lived in Ireland, the United Kingdom and northern France 2,000 years ago. Back then, the Celts donned costumes and lit bonfires to protect themselves from spirits. They believed that on the last day of October, the dead were free to roam the earth before they returned to their rightful place in the other dimension.

The Halloween we are currently familiar with is a mix of beliefs and customs of American Indians and ethnic groups from Europe. Halloween became especially popular during the latter part of the 19th century when millions of Irish immigrated to America.

Photo by Matej Novosad from Pexels

Photo by Matej Novosad from Pexels

Undas Culture

For us Filipinos, Halloween is merely party of a more solid tradition called Undas which, many speculate, is derived from the Spanish word honra meaning respect. From October 31 to November 2, we honor the dead in major ways.

Many travel to the provinces to visit the graves of their deceased. In cemeteries, visitors pitch tents even before October 31 to spend the night—or several nights. Memorial parks become venues for family reunions with potluck food. Some practice pag-aatang or offering food to the dead by placing it on their graves. Meanwhile, those at home light candles on doorsteps in the belief that these will guide lost souls toward the light of the after-life.

Pangangaluwa

If the West has its trick-or-treating, we have our own custom called pangangaluwa (souling). The original practice involves elders, who upon returning from the cemeteries on the evening of November 1, would wear white blankets to represent the spirits. When midnight struck, they would go from house to house, singing traditional songs and appealing for donations and prayers for the departed souls. Their eerie costumes and voices in the dark made for a hair-raising experience.

Sariaya in Quezon has revived pangangaluwa, a project initiated by the Sariaya Tourism Council (STC) in 2005 to raise funds for the town’s Belen Festival during Christmas. From October 27 to 30, young people dressed in ghoulish costumes visit neighborhoods. Like Christmas carolers, they serenade residents, who have been informed beforehand of the visit and solicitation of funds.

A scene from Biag ni Lam-an at the 2019 Semana ti Ar-Aria Festival (photo from the festival’s FB page)

A scene from Biag ni Lam-an at the 2019 Semana ti Ar-Aria Festival (photo from the festival’s FB page)

Semana ti Ar-aria Festival

In Ilocos Norte, the Semana ti Ar-Aria Festival is a weeklong celebration that attracts tourists from neighboring provinces and Manila. Ar-aria is Ilocano for ghost; but the festival does more than remembering the dead, it also involves art-related contests and activities. This is because events are tied up with the birth anniversary of political activist and renowned painter Juan Luna, who was born in Ilocos on October 23, 1857.

On its 9th year last 2019, Semana ti Ar-Aria highlighted Ilocano folklore, such as Biag ni Lam-ang (The Life of Lam-ang), an epic poem about an extraordinary warrior who is aided by magic during his quest for his father. The celebration’s highlights also included the Taray Ar-Aria (zombie run), trick-or-treating and street dancing.

San Antonio locals depict the Plaza Miranda Bombing in 1971, which killed 9 and wounded around 95 people, including senators. (photo by Jazel Kristin)

San Antonio locals depict the Plaza Miranda Bombing in 1971, which killed 9 and wounded around 95 people, including senators. (photo by Jazel Kristin)

Tumba-Tumba Competition

During Undas, San Antonio in Zambales becomes a macabre-looking neighborhood as residents dress up street corners to depict death scenes in time for the annual Tumba-Tumba Competition.

Tumba, Spanish for tomb, originally referred to shrines for the dead, peppered with flowers, candles, and images of saints. But with the Tumba-Tumba Competition, the tombs have evolved into homes converted into horror houses, sometimes complemented by dancing zombies and scary creatures perching on trees.

Jazel Kristin, who was once a judge of the competition gives us an idea of how grand the displays can get. “I’m always impressed by the effort that the community puts into them. They show the creative spirit of the Zambaleños in their depiction of everything, from horror movie characters to indigenous mythological creatures. They show familiar scenarios like capsized tourist boats, and political issues like the Ampatuan Massacre, Plaza Miranda Bombing, ISIS and the drug war.”

Locals re-enact the 1996 Ozone Disco Fire rendition before the tragedy. (photo by Geric Cruz)

Locals re-enact the 1996 Ozone Disco Fire rendition before the tragedy. (photo by Geric Cruz)

Jazel’s criteria for judging includes originality, creativity and effectiveness of storytelling driven by production design, involving sound, music, make up, costumes and props. “It’s a long night with people going in and out of the tumbas. So the actors always have to be in character to make their world believable.” For Jazel, the most memorable tumba she has seen is the recreation of the Ozone Disco Tragedy, acknowledged as Philippine history’s worst fire, which killed at least 162 people in 1996. “There was this house playing some music, a mirror ball hanging on the ceiling and under it were teenagers dancing, all covered in colorful strobe lights. When we returned the next day of judging, we saw all of them lying on the floor—a recreation of the Ozone tragedy. Simple execution but effective storytelling.”

Locals re-enacting Ozone Disco after fire (photo by Geric Cruz)

Locals re-enacting Ozone Disco after fire (photo by Geric Cruz)

Jazel considers the Tumba-Tumba competition as a creative way to bring the community together. “It gives people something to look forward to. It also gives us a peek into how certain events affected themm and how they use this tradition to shed light on tragedies and disasters, reminding people that yes, they did happen.”

With COVID-19 still rampaging across the globe, death has become a daily update in the news. But with these local customs, we see an underlying endeavor to better understand death, to see its many faces, and perhaps, come to terms with its true nature—about how death really is not the opposite of life, but an inevitable part of it.

One night, fifteen years ago, Lea was flipping through the channels on her television, looking for a movie to help her destress from her job as a financial adviser in one of the country’s top insurance companies. Instead, her channel surfing took her to a show on yoga, which kept her glued until the end. Watching the gentle flow of yoga poses helped relieve her stress, which kept her tuning in to the show regularly, until she found herself practicing yoga. “I fell in love with yoga since then. I loved how it had a holistic approach to health, focusing on both physical and mental abilities.”

For ten years, she dabbled with yoga until five years ago when she decided to make it her daily practice. “At that time, I was feeling exhausted and stressed. My body was pleading for a break. I decided to focus on myself.” With her regular yoga practice, Lea discovered a more focused way of thinking, and with this clarity came the realization of what she wanted to do with her life. “Two years ago, I decided to go to Vietnam to undergo training so I could be a yoga teacher. Our yoga class had five teachers, which we called masters. We would start our practice with pranayama, or breathing exercises coupled with meditation. It taught me to focus on my breath and to be still in the present. In the stillness, I could hear what my mind and body were telling me.”

Her six-month training certified Lea as a yoga teacher. Because of the pandemic, Lea holds online yoga classes, not just for Filipinos, but also for friends she made in Vietnam. At the same time, she supports her husband in developing an organic vegetable garden in Rizal. He focuses on growing high-nutrient fruits and vegetables that complement Leah’s yoga practice. Though Lea is living proof of yoga’s ability to help regulate blood pressure, fight insomnia and support the body’s natural healing process, she finds that the most important thing she gained from her practice is mental strengthening. “A weak mind can’t carry a strong body, but a strong mind can carry even the weakest body,” she shares. “A strong mind will keep you stable and grounded. It gives you the power to cope with stress.”

This October 14, Lea will share simple breathing and meditation exercises in Panahon TV’s much-awaited webinar, Peace of Mind during the Pandemic, which also features psychiatrist Dr. Rowalt Alibudbud, and Dr. RJ Naguit, chairman of the Youth for Mental Health Coalition, Inc.

From this webinar, Lea hopes that participants will learn to let go of things they can’t control. “Stress is inevitable, but what’s more important is that you know how to manage it. If you’re on a continuous fight-and-flight mode, you’ll get sick. Gentle yoga helps release the tension with mindful poses. Just by focusing on your breath, you honor your body, allowing acceptance, awareness and letting go. When you do this daily, you develop a calm state of mind. It’s a powerful tool to manage everything that’s happening in the world today.”

To register for the webinar, click here: https://panahon.tv/webinar/index.php

As the country struggles against the pandemic, the solution to combat COVID-19 seems to be the use of plastic and other disposable materials. Jeepneys, tricycles, buses and trains use plastic dividers to promote physical distancing among passengers; and since August 15, The Department of Transportation has mandated the populace to wear—along with face masks—face shields, usually made from plastic, when taking public transportation. Adding to the plastic burden is the deluge of food take outs and merchandise deliveries, deemed the safer option than dining out or going to malls during the pandemic.

Inside a jeepney in Bulacan (photo by PM Caisip)

Inside a jeepney in Bulacan (photo by PM Caisip)

But the Philippines isn’t the only country boosting waste production. In Thailand, home deliveries account for the increase of plastic waste from 1,500 tons to 6,300 tons per day. Last February, China ramped up its daily face mask production to a staggering 116 million daily, resulting in hundreds of tons of used masks in public bins each day.

Hospitals are also generating more waste. According to the Asian Development Bank’s data last April, Metro Manila hospitals, which deal with more than half of the country’s COVID-19 cases, were estimated to produce 280 metric tons of medical waste each day. A similar number was reflected last March in Wuhan hospitals, which produced more than 240 tons of daily waste at the height of the outbreak, compared with 40 tons during ordinary times.

Garbage in Misamis Oriental (photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Garbage in Misamis Oriental (photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Plastic Pollution

The United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment) states that even before the COVID-19 pandemic, a million plastic drinking bottles were purchased every minute across the globe. Each year, up to 5 trillion single-use plastic bags are used worldwide, while 8 million tonnes of the world’s plastic end up in the oceans.

Plastic is widely produced and used because they are durable and don’t break down. Ironically, these traits are also the reason why they’re harmful to us and the environment. According to the UN Environment, most plastic items in the oceans are broken down into tiny particles easily swallowed by marine animals—the same animals that humans eat. Plastic has also found its way into our tap water, increasing our risk for ingesting them. By clogging drainages, plastic facilitates breeding grounds for pests, which give rise to vector-borne diseases such as dengue and malaria.

Plastic in the Philippines

According to a 2015 report released by the Ocean Conservancy, the Philippines ranks third among the world’s top plastic polluters of oceans.

But efforts to address rampant plastic use has been shelved due to the pandemic. In fact, the Quezon City government is thinking of suspending its ordinance on banning single-use plastic and disposable materials. But Greenpeace Campaigner Marian Ledesma emphasizes that such move can greatly impact an already ailing environment and population. “Single-use plastic is not inherently safer than reusables as it will cause additional public health concerns once discarded,” she says. “As the government gradually allows businesses to reopen, reusable systems and single-use plastic bans must be implemented to ensure the protection of the environment, workers, and consumers.”

Garbage from South Korea dumped in Misamis Oriental (Photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Garbage from South Korea dumped in Misamis Oriental (Photo by Manman Dejeto/Greenpeace)

Compounding the nation’s plastic crisis is the illegal waste trade. Since China stopped its waste importation, Southeast Asia has received a deluge of toxic garbage from developed countries. In the last three years, the ASEAN region, notably Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, saw an astounding 171% growth—equivalent to over 2 million tonnes—in plastic waste imports. Data from Greenpeace Southeast Asia shows that from 4,267 tons in 2017, plastic waste imports to the Philippines rose to 11,761 tons in 2018. Most of these came from Japan, the United States, Taiwan, Indonesia, and Hong Kong.

Last year, the government began shipping back the controversial Canadian garbage, which slipped into the country between 2013 and 2014. The shipments, labeled as recyclable materials, was, in fact, made up of 64% unrecyclable residuals.

But NGO groups such Ecowaste Coalition and Greenpeace Philippines believe that the uncovered shipments show only the tip of the iceberg of waste that actually enters the country. They have been calling for the government to sanction the Basel Ban Amendment, which bans the import of all waste, including those for recycling. “The ratification of the Basel Ban Amendment (BBA) and the enactment of a total ban on waste imports is crucial, especially at a time when the nation grapples with recovery from a global pandemic that has led to the proliferation of medical and household waste,” Greenpeace Country Director Lea Guerrero said. “Lack of prohibitions on waste imports and poor enforcement of existing regulations leave the country open to future incidents of illegal waste trade, which often results in recipient countries shouldering the health and environmental costs of foreign waste.”

Enterprising Pinoys, including Eli/sew/beth, are making and selling reusable face masks

Enterprising Pinoys, including Eli/sew/beth, are making and selling reusable face masks

Go for Reusable, Not Disposable

A study published in Environmental Science & Technology states that an estimated 129 billion disposable masks and 65 billion disposable gloves are used worldwide each month during the pandemic.

This concern has prompted over 130 global health experts—including scientists, academics, doctors, and authorities on public health and food packaging safety— to sign a statement that assures the public that reusables, when coupled with basic hygiene, are safe during the pandemic. In an interview with Greenpeace Philippines, Dr. Geminn Louis Apostol of the Ateneo School of Medicine and Public Health stated that the pandemic waste has led to widespread environmental contamination, as well as increased public health risk. “Inequitable access to PPE (personal protective equipment) and to information about how to stay safe has contributed to the disproportionate rates of infection in poor and minority communities. If medical masks are prioritized for healthcare workers, the general public can use cloth masks as a safe, cost-effective alternative.”

Though health and safety is a pressing issue during the pandemic, outbreaks have long been linked to environmental degradation. By lessening our waste during these challenging times, we also lessen our risk for sickness. As Dr. Renzo Guinto, a physician and public health expert on health, climate change, and the environment, stated in an interview, “Protecting the public’s health must include maintaining the cleanliness of our home, the Earth. We don’t need to choose one over the other – we can protect ourselves from COVID-19 while protecting the environment.”

According to Johns Hopkins University, over 19 million people have contracted COVID-19 as of August 9, 2020. The Philippines has a total of 129,913 confirmed cases—of which 59,970 are active, 2,270 are deaths, and 67,673 are recoveries.

Each day, the Department of Health holds press briefings and closely works with a task force that has worked diligently since its creation. The Philippines now ranks number 1 in testing capacity in Southeast Asia for confirmed and active cases.

With our increase in testing capacity, full health campaign for combatting COVID-19, and a cooperative nation wearing masks, what else is missing? Given these measures, the Philippines should be having less cases.

Getting the Fundamentals Right

Filipinos seem to be overwhelmed with the deluge of instructions as well as misinformation and disinformation. Though the Department of Health(DOH) is endorsed as the official source of local data, and the World Health Organization for global data, there are just to many well-meaning people who forward unverified information.

DOH sought a new endorser, the popular actor, Alden Richards, to proclaim its new campaign—BIDA Solusyon. It’s a catchy phrase, playing on the Filipino word bida, which means “the lead star”. BIDA Solusyon, which wittingly sounds like “Be the Solution”, shows in part animation how to combat COVID-19. BIDA serves as an acronym for four steps:

B – Bawal walang mask.

I – Isanitize ang mga kamay; iwas-hawak sa mga bagay.

D – Dumistansiya ng isang metro.

A – Alamin ang totoong impormasyon.

The messaging is light and friendly, and easy to digest.

Gaps in the Messaging

But the acronym, though clever, seems to be missing a step in achieving ”minimum health standards”. Before wearing a mask, one should wash hands properly with soap and water, scrubbing them for at least 20 seconds as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention before rinsing. When one uses dirty and infected hands to put on the mask, the preventive measure becomes ineffective.

The public’s proper and consistent compliance spells the difference between life and death. But with this massive campaign on handwashing and hand sanitizing, there is also a need to consider areas with no running water and basic facilities for sanitation. How can people wash their hands with water and soap when there’s no water to begin with?

Masking the Problem

The WHO has already approved cloth masks as basic protection. This cannot be emphasized enough: masks need to be worn at all times outside the home, especially when one is in an enclosed space with other people.

Proper use of the mask means having the nose and face covered and securing it under the chin. Make sure the sides of your face are covered, but also check if you’re breathing easily. Don’t let it rest on your chin or forehead as contact with exposed skin may result in a contaminated mask.

After using a disposable mask, remove it from behind and discard it in a closed bin. Make sure to wash cloth masks after use. And most importantly, wash hands with soap and water after using masks.

The words to remember when wearing masks are properly, correctly, and consistently.

Utilizing TV for Information

According to Digital 2019, a report from Hootsuite and We are Social, 76 million Filipinos are internet users, all of them on social media. But our internet speed remains at a dismal 19 mbps, a tenth of Singapore’s fixed connection speed of 190.9. Also, there are still areas in the Philippines without proper internet infrastructure and poor cellular signal.

At this time, the government has to fully utilize its TV and radio broadcast channels to disseminate information on health, agriculture, and entrepreneurship. To retool and upskill citizens, trainings from the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA), and even first aid, can be broadcast through mass media—with testing and accreditation to be done in barangays.

Going Analogue

The DOH recently launched an app for contact tracing. Upon a recent audit, the country’s new contact trace czar Benjamin Magalong found the contact tracing system of cities and barangays lacking.

But even in our own homes, we can employ our own simple system with just a piece of paper and a pen. By dividing the paper into columns of Date, Time, Venue, Activity and People We’ve Interacted with, we can maintain a contact trace system in our household, making it easier for authorities to respond should one be confirmed positive for COVID-19.

Getting the Basics Down Pat

Going back to basics, getting the fundamentals right is a simple exercise that we can all do. Ask yourself today—did you wash your hands properly? Did you wear your mask properly?

Perhaps our leaders can also ask themselves—is everyone equipped with running water to ensure their health and safety? What is the best way to disseminate information? Does everyone have a home to seek refuge in while the deadly virus roams freely outside? Before we run, we need to first walk. Before we can help save lives, we must be able to help ourselves first.

The COVID-19 pandemic is teaching us lessons the hard way, but with proper planning, we don’t need to learn them the hard way.

Donna May Lina

9 August 2020

New Zealand has recently created buzz for its response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Its management of COVID-19 has been considered by experts as one of the best and most effective, leading to low numbers of positive cases and fatalities.

On February 3, 2020, the New Zealand Government placed entry restrictions on foreign nationals traveling from Mainland China, weeks before the World Health Organization (WHO) had a name for the disease.

The first case of COVID-19 in New Zealand was reported on February 20, 2020.

On March 21, 2020, the New Zealand government introduced a four-level system to help fight COVID-19. The country was then placed under Alert Level 2.

On March 23, New Zealand was placed under Alert Level 3, following reports of community transmission of the virus.

On March 25, a state of emergency was declared, and Alert Level 4 was raised, placing the country under lockdown.

On March 29, New Zealand reported its first COVID-19 related death.

The alert levels were gradually lowered as the number of new COVID-19 cases began to lessen. On June 8, New Zealand reported that there are zero active cases in the country, moving to Alert Level 1. As the alert level was lowered, a few positive cases were reported, some with a history of foreign travel.

There are currently some 80,000 Filipinos in New Zealand. Let us take a look at one Pinoy’s experience as restrictions there are lifted: https://youtu.be/cK0L1gyqPQU

Kathy San Gabriel / Panahon TV Reporter