Metro Manila’s first few days under General Community Quarantine (GCQ) saw a deluge of commuters being stranded with no sufficient public transportation. But the urban commuter’s burden has long been an issue even before the pandemic.

Caryn, a resident of Tondo in Manila, recalls a particular incident that stood out in her more than twenty years of commuting. “Once, I was in Pasig when the MRT broke down and we were advised to take the bus across the street. I was so surprised to find out there wasn’t a bus stop. There were no lines—it was a free-for-all kind of thing. People grabbed the railing and pulled themselves up onto the bus, while the conductor kept yelling for people to hurry up because the traffic enforcers were coming.”

Aloy, who’s been commuting since she was twelve and is now a mom, has a collection of horror commuter’s stories. “Around 2003, I was sitting in a taxi in the middle of traffic, painfully aware that I was missing my friend’s wedding to which I was supposed to be the lector. In 2005, when MRT was getting more crowded, I remember being forced to press against a total stranger—male, as luck would have it. In 2016, I was stuck in one of those triple whammy carmageddon nights of floods, mall sale and payday. I was forced to stay over at a friend’s home until 11 p.m. before I could go home to my family, which included a breastfeeding baby. I think about all the time traffic has stolen from me and my family, and I find it unacceptable.”

Biker wears a face shield attached to his helmet (Photo by Jire Carreon)

Biker wears a face shield attached to his helmet (Photo by Jire Carreon)

Hitting the road

In 2010, the World Bank noted an increase in energy consumption from the Philippines’ transport division, making up about 37% of the country’s total energy consumption—most of it coming from road transportation.

But with the declaration of the Enhanced Community Quarantine (ECQ) two months ago, people were discouraged from leaving their homes and public transportation was banned, resulting in empty roads. With essential businesses such as hospitals, pharmacies and food markets continuing operations, employees and consumers who didn’t own cars rode bicycles or walked.

Danielle Guillen, an urban transport planner and professorial lecturer at the University of the Philippines Diliman’s School of Urban and Regional Planning and Asian Institute of Tourism, makes this observation: “I think the ECQ showed that active transport is doable in Metro Manila if there are few motorized vehicles on the road. The ECQ really brought back the road space for people. Active transport (biking and walking) is only doable if we have enough road spaces that are connected, safe, and green shared with pedestrians and cyclists. Aside from the hard infrastructure that includes people-friendly designs, the soft infrastructure should be there. This means building the culture where motorists respect pedestrians and cyclists like what we see in most developed countries. This would mean embedding prioritizing transport ethics in our educational and motor vehicle registration systems.”

Bike and pedestrian paths in Tsukuba, Japan (photo by Caryn Santillan)

Bike and pedestrian paths in Tsukuba, Japan (photo by Caryn Santillan)

Parked bikes in Amsterdam, Netherlands (photo by Johan Marten)

Parked bikes in Amsterdam, Netherlands (photo by Johan Marten)

How other countries do it

During the quarantine, biking and walking for most people was a novelty. But in other countries, such forms of active transport have always been the norm.

Caryn, who lived in Japan for more than a decade, shares that Tokyo train stations provide overnight parking lots for bicycles so employees could bike from the station to their offices in the morning. “Active transport is very much integrated into their way of life. Very early on, kids are taught to walk to school. They were allowed to use a bicycle to commute when they were old enough. Some bicycles are fitted with attachments for transporting one to two preschoolers, or have baskets for groceries. The bikes have safety features, and need to be registered at the local ward office.”

For seven years, Aloy lived in the Netherlands, where active transport is the default lifestyle with children learning to bike as early as two years old. “Some families even have different kinds of bikes—the everyday, inexpensive one for daily trips to work, errands or visiting friends; and the fancier, sturdier bikes for long-distance weekend trips. There are cargo bikes for carrying your little ones, and e-bikes for older members whose knees are getting weaker.” Because of this, rush hour in the Netherlands looks a lot different from Manila’s carmageddon. “Rush hour in the Netherlands is a swarm of bikes. Bike infrastructure is everywhere. In any party or gathering, I’m guessing that more than 80% of the people came in bikes.”

Caryn in Tokyo, Japan

Caryn in Tokyo, Japan

But in both Japan and the Netherlands, bikes are not the only kings of the road. In Japan, non-bikers like Caryn find it a breeze to walk. “Since most sidewalks are wide and clean, walking in Tokyo wasn’t a hardship—even in heels! When we moved to Tsukuba, which is about an hour away from Tokyo on the express train, I usually walked. It takes around 20 minutes for me and my kids to walk to the city center, but the pedestrian and bike paths are clean and very picturesque.”

Aloy and Bram rode a cargo bike during their 2011 wedding in Netherlands

Aloy and Bram rode a cargo bike during their 2011 wedding in Netherlands

Aloy shares how the Dutch view walking, not just a means to get somewhere, but also a leisurely social activity. “It helps that there are so many parks. I feel that Dutch cities disincentivize car ownership by keeping roads small, maintaining high taxes on cars, taxis and parking fees, and maintaining bike paths with real barriers and bike stoplights.”

Aside from enabling Filipinos to easily clock in the recommended daily ten thousand steps to maintain good health, active transport also allows commuters greater mobility amid the pandemic. “It is the only means for us to really practice social distancing,” Guillen shares. “Walking is the very first mode of mobility that we could really control. Next is cycling, considered an advanced form of walking. If we have a really good walkway or cycling path infrastructure and space, we can easily estimate if we are two meters away from the others.”

Beyond walking and cycling

Aside from active transport, Guillen acknowledges the need for community public transportation that’s both safe and eco-friendly during the pandemic. “Other forms of public transportation would be busses and trains—as long as the social distancing and related health protocols are enforced. For short-distance trips, single-passenger pedicabs and tricycles are an option. However, it is important to note that the old jeepney does not really meet the public transport utility vehicle design standards. The government’s PUV(Public Utility Vehicle) modernization goal, if I understood it correctly, is to really update in terms of design and make the service meet service-level standards. With the pandemic, design and service should now consider social distancing and related health protocols.”

Even beyond the pandemic, Caryn wishes that the Philippine public transport will be a great equalizer like in Japan. “Train passengers are a mix of teenagers, suited businessmen, mommies pushing baby strollers, kimono-clad old ladies, and women in formal evening wear and fur coats,” recalls Caryn. “There are facilities for the disabled—elevators for wheelchairs, tactile paving, braille signs, and audio announcements (in different languages) for the visually impaired. And I greatly admire the pride instilled in their public transport employees. They all know they are part of an important system that helps the city run. They do their job competently and treat passengers respectfully.”

Aloy describes the Netherlands’ public transport system as a “well-oiled machine. When it falls out of schedule with a delayed train, you can hear the deep, deep disappointment rumbling through the crowd, because they are so used to efficiency. I was once on a train where the conductor apologized over the public system that we were arriving five minutes early at the destination.”

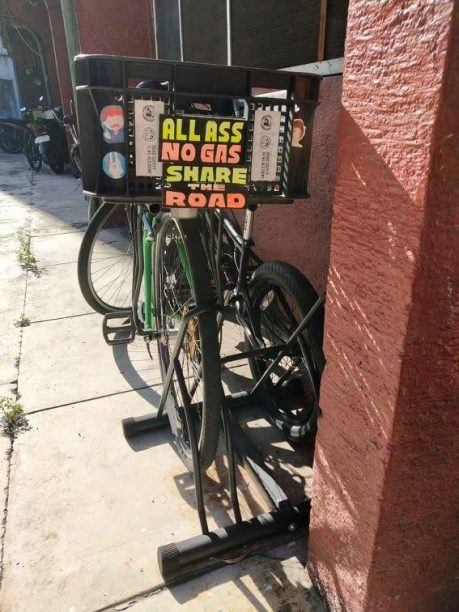

Bike placards (photo by Agay Llanera)

Bike placards (photo by Agay Llanera)

Wishlist for Manila’s public transportation

There is no doubt that the surge of private vehicles in Manila’s roads compound traffic. But why are urban Filipinos so car-centric? Guillen explains, “I think this a product of our long history where building highways was prioritized over the rails, as well as the culture that somehow equate car with economic development. Advertisements to market new vehicles could also play a role. Moreover, there is also the sad reality that public transport and options for active mobility are quite limited. To improve the existing public transport system, there should be enough supply during peak hours and off-peak hours. The system should also consider the active transport component of the whole mobility experience.”

A volunteer assisting bikers during the pandemic (Photo by Jire Carreon)

A volunteer assisting bikers during the pandemic (Photo by Jire Carreon)

Aside from proper bus stops that are strictly followed, Caryn hopes for more waiting areas for commuters, including persons with disabilities (PWDs). “Imagine waiting for a bus under the midday heat or while it’s raining! Also, now that more people are using bicycles, bicycle theft has become a big issue. Establishments should provide secure parking racks— and wider, safer, well-lit sidewalks please, with no vendors taking up the space where people ought to pass. Most of all, I wish we would follow through with urban transport plans despite the changes in administration.”

Aloy wishes for a public transport system that allows commuters to enjoy their travel. “I try to imagine what commuting looks like to a 3-year-old— all 95 centimeters— and it must be frightening. As sociable as we Filipinos are, living in Metro Manila has not made it easy to meet up with friends. If I wanted to enjoy an after-work dinner with a small circle of friends, very few would agree to make it. The city and its transport system simply don’t allow for those connections to be nurtured.”

For Guillen, a country’s public transport system reflects the values of its government and its people. “A country with an exemplary public transportation system means it is a country that truly cares, prioritizing people’s inclusive mobility in the overall system. It is a truly democratic country that provides options to its people on choosing one that truly meets the environment, climate change, and health concerns.”

Jeepneys have been a common means of travel and transportation for Filipinos since the American military vacated the country after World War II. From the hundreds of surplus jeeps sold or given to locals, the jeepney was born. Decades later, it continues to be part of our culture and everyday commute.

But as helpful as jeepneys are to the community, they come with their own risks. According to the Environmental Management Bureau, jeepneys contribute to 80% of the air pollution that harms the environment, commuters, and the drivers themselves. Most jeepneys are not well-maintained; some do not have working speedometers, signal lights, and even brake lights, which can cause road accidents and traffic build-up.

It is because of these factors that the Department of Transportation (DOTR) and the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) are proposing a jeepney modernization program, which aims to improve the country’s jeepney system. Last June, Secretary Arthur Tugade signed the Omnibus Franchising Guidelines in line with the country’s public utility vehicle (PUV) modernization program. The pilot program will kick off in Metro Manila in the fourth quarter of this year, followed by Metro Cebu, Metro Davao, and the rest of the country.

Here’s what the DOTr hopes to achieve with their program:

The images below are the proposed prototypes of modern jeepneys shown during the 1st Philippine Auto Parts Expo (PhilApex) last October 12, 2017.

Counter clock-wise: 1) e-jeepneys making it easier for people with disabilities to commute; 2) e-jeepney’s design similar to that of its traditional counterpart; 3) signs for jeepney stops; 4) beep cards as a mode of payment for jeepney fares.

DOTr also shares that prototype vehicles have a 22-passenger seating capacity or more, while the traditional jeepneys can seat only around 20 to 22 passengers, excluding the driver.

However, the implementation of the PUV modernization program is met with skepticism.

Abon Almares, a jeepney driver for 15 years, believes e-jeepneys are too expensive. “Tutol ako doon kasi yung mga mayayaman at may pera lang ang may kakayahang bumili niyan. Sabihin nating kalhating milyon ang ganitong jeep at dalawang milyon yung electronics, kung hindi ko na nga kayang bumili pa ng ganitong jeep at sa kikitain ko, paano pa ako bibili nun? Dapat ang iphase out lang nila ay yung mga luma na talaga at delikadong mga jeep.” (I am opposed to the modernization because only the rich can buy the new jeepneys. Let us say that the price of this jeep is half a million and the new jeep is two million; if I can’t buy this jeep with what I earn, how can I even buy the new jeepneys? They should phase out only the old jeepneys and those that don’t function anymore).

According to the DOTr, the PUV modernization program is not anti-poor with its rates of 6% interest and 5% equity. Aside from its 7-year repayment period, the government will give subsidies of PHP 80,000 for every unit to help with the downpayment.

But for jeepney driver Benjamin, the e-modernization is an insult to our culture. “’Di ako pabor kase iyan na yung kinamulatan natin parang ano yan eh, parang sagrado ‘yan.’Yan kasi ang unang tranportasyon natin ‘di ba, yung jeep. Kaya kung tatanggalin yan, maraming maapektuhan.”

(I am not in favor with the modernization because jeepneys are part of our culture and our first mode of transportation. So, if they phase it out, a lot of people will be affected.)

He’s also concerned with the fate of old jeepneys. “Ang tanong ko diyan, kung gaano rin katagal yung ipapalit nila? Anong mangyayari sa mga ipphase-out na jeep? Tutunawin ba yun ulit or saan nila itatapon? Tsaka akala ko ba nagtitipid sila ng kuryente? Mas lalong hindi sila makakatipid ng kuryente sa ganyan.”

(How long will the new jeepneys last? What will happen with the phased-out jeepneys? Will they melt them or dump them somewhere? Also, I thought they wanted to conserve electricity? They will consume more if they use it for the modernization.)

“Dapat pag-aralan nila nang husto. Hindi naman sa ayaw talaga namin yung upgraded mas maganda kung mapalitan ng ano kaso nga lang masyadong mabusisi. Sa kagaya ko kung hindi makakakuha ng unit, paano? Yung mga may pera, sila yung unang mabibigyan.”

(They should study this issue more. It’s not that we’re completely against it. It would be beneficial for us if it would be replaced but with due process. Also, they should study the details. How can a driver like me afford a unit? Those who have the money will be the first ones to acquire the new jeepney.)

The jeepney modernization program shows promise in aiding the community’s transportation problems. But for it to truly work, both sides must be willing to work together. When the issues are ironed out, everyone will benefit. Finally, the jeepney will be known, not only as “King of the Road”, but also a champion of the environment.

– By Panahon TV Intern, Czekinah Tolentino

Online References:

https://www.vecteezy.com/vector-art/134986-jeepney-in-the-summer-time